===

WALL STREET JOURNAL

ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT

Britain’s Royal Academy Surveys Anselm Kiefer’s Work

Preoccupied by politics and history, the German-born Anselm Kiefer is getting a retrospective at Britain’s Royal Academy

Anselm Kiefer often uses unusual materials including straw and real blood to confront Germany’s past.DPA/Zuma Press

By MARY M. LANE CONNECT

Sept. 18, 2014 4:09 p.m. ET

The Works of Anselm Kiefer

View Slideshow

Anselm Kiefer often uses unusual materials including straw and real blood to confront Germany’s past. DPA/Zuma Press

In the late 1960s, when German artist Anselm Kiefer was in his early 20s, he owned recorded speeches by Adolf Hitler and other Third Reich leaders. The Allies had distributed the recordings after World War II in a move to encourage reluctant Germans to confront their Nazi past.

For Mr. Kiefer, now 69, the impassioned speeches acted as a trigger: He would use his art as a weapon to fight social amnesia. “Now you can turn on German TV and there’s likely to be a documentary about the war. When I was growing up in the 1960s you didn’t even talk about it,” says Mr. Kiefer.

In 1969, wearing his father’s military uniform, the artist had himself photographed giving the banned Nazi salute and bound the photos along with Nazi-themed watercolors into two cardboard books. The performance launched a career that would remain dominated by Mr. Kiefer’s preoccupation with Germany’s past and the nation’s politics.

Both books are part of a retrospective opening at London’s Royal Academy on Sept. 27 and running until Dec. 14. The exhibition documents how over 40 years the France-based artist has employed such materials as oil paints, straw and electrolyzed lead to convey his mostly grave messages.

The Nazi salute quickly disappeared from his work, and some art in the show touches on more neutral themes, such as “Osiris and Isis,” a large 1985-87 work of oil and acrylic emulsion exploring the nuances of ancient Egyptian mysticism. But Mr. Kiefer has kept returning to Nazi Germany, albeit often in oblique ways. ” Georges Bataille : Blue of Noon,” a new set of watercolors and pencil on plaster, alludes to a prewar erotic novella by the 20th-century French writer in which a group of Hitler youths plays a peripheral role.

“I hate that I’m using this clichéd phrase but he’s very much an ‘intellectual artist,’” says Kathleen Soriano, the show’s curator. Ms. Soriano, 51, says she decided against explanatory wall captions to avoid “hitting visitors over the head with all the meanings in the show” and limited such clarification to the catalog.

Visitors unschooled in the artist’s obscure references may be left to focus on the artist’s often unconventional materials, both Mr. Kiefer and Ms. Soriano say. In “Parsifal III,” a 10-by-14-foot work on paper from 1973, Mr. Kiefer used a mixture of paint and blood. This image, which addresses Wagnerian themes adored by Hitler, aims to “rehabilitate” artists like Wagner from the blemish of Nazi worship, Mr. Kiefer says.

A similar-size work, “Margarethe,” was created using gray and white paints mixed with straw Mr. Kiefer found in a cornfield. Mr. Kiefer says the work was inspired by the poem “Death Fugue” by Paul Celan, a Jewish poet jailed by the Nazis. “My art… changes not only because the materials like straw change over time, but also because since they concern themselves with history, the world views of those looking at it are unavoidably different as the decades pass,” he says.

Ms. Soriano says she’s dedicating two rooms in the show, including the first, to Mr. Kiefer’s delicate watercolors. Mr. Kiefer’s Paris-based dealer Thaddaeus Ropac welcomes the move. Mr. Ropac, 54, only offered one watercolor in his latest exhibition. It sold for $65,000, far below the $650,000 to $5.8 million for large paintings. “The watercolors are still such virgin ground,” he says.

As he awaits his retrospective, Mr. Kiefer says he can never begin to answer one question: Would he have been a Nazi? “Naturally I hope I would have said ‘I’m fighting against Hitler.’ But I can’t say for certain if I had lived then, what I would have done or decided.”

==

All my doubts about Anselm Kiefer are blown away by his Royal Academy show

‘Winter Landscape (Winterlandschaft)’, 1970, by Anselm Kiefer

In the Royal Academy’s courtyard are two large glass cases or vitrines containing model submarines. In one the sea has receded, dried up, and the tin fish are stranded on the cracked mud of the ocean floor. In the other, the elegantly rusted subs are mostly suspended like sharks in an aquarium: a fleet in fact, all pointed in the same direction.

These works are the visitor’s first sight of the vast and glorious exhibition by Anselm Kiefer (born Germany, 1945) currently occupying the main galleries of Burlington House, and they are apparently related to his interest in the Russian poet and futurist Velimir Khlebnikov. At once we are confronted by several Kiefer themes: war, poetry (he says poems are ‘like buoys in the sea. I swim to them, from one to the next …without them, I am lost’), and Mesopotamian clay tablets. His very particular mix of history, imaginative transformation and high culture is thus succinctly introduced.

There have been plenty of opportunities to see Kiefer’s work in Britain in recent decades (I well remember an impressive show of giant lead books at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith in 1989), but I must admit that up to now I have remained equivocal about him. The Academy’s show has completely changed my mind. I have never seen Kiefer better presented, and in this exhibition his imagery and use of materials make perfect sense. The increasingly large works have been superbly laid out through the grand galleries, and their cumulative effect is not so much overwhelming as utterly convincing. This remarkable display makes a great argument for the monographic exhibition. Not all artists can survive this sort of exposure, some looking too repetitious or threadbare in extensive solo shows, but Kiefer’s work thrives on it, and the exhibition is a triumph.

The first couple of rooms offer a kind of prologue of early work, introducing Kiefer’s abiding passion (since 1968) for artists’ books, his drawings and watercolours, and the wood-grain ‘Attic’ series of the 1970s. The exhibition really catches fire in room 3 with the increased scale and texture of the paintings, the inventive use of materials (clay, ash, earth, straw, dried sunflowers, scorched photos) and a certain salutary grimness of subject. Here the aggrandising tendency of Nazi architecture is squarely faced, the neoclassical stone structures built to last (and make fine ruins), as against the bricks of straw and the writing on the wall of the artist’s alternative reality. If some of the paintings look like dried-up river beds, suggesting drought and starvation, this is the other side to handsome prisons of the spirit.

Kiefer uses the shape of a palette in his pictures to stand for himself, and I was reminded of Leonard Cohen’s lyric ‘like a bird on the wire/ Like a drunk in a midnight choir’ when looking at ‘Palette on a Rope’ in room 4, though there’s more than one bird on this particular wire, and they look decidedly flame-like. Room 5 contains just two enormous paintings: ‘Osiris and Isis’ on one side, decked out with copper wire and what looks like the fragments of a washbasin; ‘For Ingeborg Bachmann: The Sand from the Urns’ is on the other, an achingly beautiful, desiccated landscape. The theme is death and resurrection, just one of the great linked polarities that Kiefer rarely shrinks from addressing.

Burnt books, branches, roses — all are incorporated in one or other of the epic paintings on display here, many of which, despite their size, come from private collections. Kiefer has a genuine interest in the mystic life, and is as likely to explore the diamond-studded firmament as he is the fertile plain. In room 11, we find Kiefer in agrarian mode, evoking ‘a land, perpetually coming to harvest’ (Ronald Johnson: The Book of the Green Man). These intensely romantic images of fruitfulness are subverted by such things as a mantrap attached to the painting’s surface — a notable vagina dentata clearly echoing Courbet’s ‘L’Origine du Monde’ — old shoes or a set of primitive scales, along with volcanic stone and gold leaf. Since the death of the Catalan master Antoni Tàpies, Kiefer must be our leading artist-magus.

Some people complain that they’re overburdened by the weight of reference in Kiefer’s paintings, the history, poetry and philosophy that inform his approach. I can only say that the viewer does not need to know or recognise its presence, nor feel inadequate before Kiefer’s learning. There is much to enjoy in his work on a purely formal level, but if you wish to explore the manifold layers of meaning below the surface, there’s even more to intrigue and savour. Then there are those who think his pictures rather rudimentary, exploiting texture and simple perspective and owing more to the mud and muck of the farmyard than to any alchemical (or artistic) transformation.

Others admire his work but regret the industrial scale on which it now seems exclusively to operate, and suggest that you can get away with murder with an adoring international market and an army of assistants. But I have to say that such quibbles dwindle and vanish in the face of this beautifully installed exhibition. It is the art that has to convince us or condemn itself, and this is a breathtaking show, a real source of awe and wonder, probably the most astonishing event of the season.

And it can be a pretty silly season too, as demonstrated by the media circus which is now the annual Turner Prize. When the prize was founded in 1984, it seemed to offer some hope of promoting excellence with such artists as Malcolm Morley and Richard Deacon winning in early years. But since the millennium, it has increasingly become the resort of installation and multimedia artists, not painters and sculptors, and this colonisation has resulted in a tragic loss of credibility. The new conceptual orthodoxy is nothing more than a current establishment fashion but its perpetrators and propagators seem bent on excluding more traditional forms of art.

The problem is that the so-called experimental art showcased by the Turner Prize is so thoroughly passé that it merely recycles ideas thought new and original half-a-century ago. But the pundits of the media still find such stale stuff wonderfully controversial and diverting. To my mind, the unholy crop of films, wallpaper, slide projections, bad writing, flags, sociological reportage and relentless pretension that makes up this year’s shortlist is intensely depressing. The banality is unredeemed. Time to abolish the Turner Prize and inaugurate a Constable Prize for Painting, and perhaps a Henry Moore Prize for Sculpture.

This article first appeared in the print edition of The Spectator magazine, dated 11 October 2014

==

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS/REVIEW OF ANSELM KIEFER AT THE RA

At the RA

John-Paul Stonard

Anselm Kiefer first came to public attention in London in A New Spirit in Painting, the exhibition held in 1981 at the Royal Academy. It’s fitting, then, that this should be the venue for the first full retrospective in Britain, curated by Kathleen Soriano (until 14 December). Kiefer has always divided critics, some taking fright at his heavy Germanic imagery, others describing the experience of his work in religious terms. It has lost none of its ability to provoke in either direction. Visitors circulate unusually slowly, silently contemplating the works. Looming at the top of the Academy stairs is a big sculpture,Language of the Birds (2013), a pile of large books made of lead sheets, interleaved with metal park chairs, surmounted by a giant pair of outspread wings, also of lead. Made from elements familiar from Kiefer’s work over the past forty years, the sculpture signals the epic journey that lies ahead.

At the heart of Kiefer’s work is an idea and image of history. For the series of photographs entitled Occupations, which launched his career in 1969, he posed in different European locations dressed in military garb and performing a Nazi salute. The claim some have made that the photographs are evidence of fascist sympathies is bizarre – the satire is obvious. Although other German artists – Gerhard Richter and Markus Lüpertz, for example – had used military imagery, only Kiefer was reckless enough to portray himself as a Nazi. Kiefer was breaking a taboo about showing the recent past, but he was also saying something about the present – about the confrontation of generations that was then taking place in West Germany. Those who were too young to have taken an active part in the Third Reich (the ‘blessed’ generation in Helmut Kohl’s phrase), were confronted with a society still dominated by collaborators. The task was to hold a mirror up to West German society, to show what it had been, and to some extent what it still was.

In paintings and books made over the next few years Kiefer seemed to plunge further down into German history, into the constellations of art and culture that had become so problematically entangled with fascism. His art is in this sense a form of unravelling.Man in the Forest, for example, a painting from 1971, is one of the first statements of his fascination with the theme of the forest and trees central to the Nazi myth. In a picture recalling Caspar David Friedrich’s The Chasseur in the Forest, Kiefer paints himself in a white gown, holding a burning branch in a thick forest, the oil layered and dripping as if the work was itself the outcome of a pagan rite.

With Kiefer there is always a sense of meanings lurking just beneath the surface, of barely hidden taboos. Four paintings from 1973 on the theme of the Parsifal legend (three are included in this show) depict an attic space, in fact Kiefer’s studio at the time, the canvas dominated by the wood grain of the interior, done in charcoal on an oil ground. Inscribed on the canvas are the names of characters from Wagner’s opera and Gurnemanz’s line ‘Oh, wunden-wundervolles heiliger Speer!’ (‘Oh wounding, wondrous holy spear!’), which puts one in mind of Albert Speer. Also inscribed are the names of members of the Baader-Meinhof gang – Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin had finally been arrested shortly before Kiefer began the work. Half-buried in the wood grain effect (a Kiefer trademark), the combination of names suggests not only ‘difficult meaning’, but also the generational conflict which was to culminate in the events of the Deutscher Herbst (German Autumn) a few years later.

Kiefer is one of the few living artists who can work convincingly on a truly monumental scale, creating vast works that seem not merely to take up, but to activate the space around them. This is particularly true of his paintings based on fascist architecture. The vast canvas Ash Flower (1983-97) is more than seven and a half metres long, and almost four in height, and shows a large ruin of what had been a classical interior in plunging single-point perspective, clay, ash and earth forming the desiccated surface. An enormous dried sunflower is attached, inverted, in the centre of the canvas. Peter Schjeldahl saw an ‘energetic contradiction of the frontal and the recessive’ in these works, which he compares to the paintings of Jackson Pollock. He refers to the sense of being caught between diving into the image, drawn into the perspectival vortex, or remaining on the surface of the canvas, seeing it as a physical object rather than an imaginary space. For perspectival recession read historical imagination, and for scarred surfaces read the historical present in which Kiefer was living and working, a Germany consumed with the task of reconstruction and, in its national life, the work of constant redefinition. According to Andreas Huyssen, this oscillation between past and present becomes a dilemma for the viewer, caught between the feeling of being ‘had’ and falling for the monumental aesthetic beguilingly presented as ‘art’. Hold onto the surface, remain in the present, if you can.

The final painting in the architectural series, Sulamith (1983), is one of Kiefer’s best-known works, and possibly his greatest. It shows a low-ceilinged vaulted chamber, based on the Nazi architect Wilhelm Kreis’s 1939 memorial hall for German soldiers. The charred walls and glowering atmosphere of Kiefer’s version, and above all the inscribed ‘Sulamith’ show that far from being a Nazi Valhalla this is a Holocaust memorial. The ‘ashen-haired’ Sulamith and the ‘golden-haired’ Margarethe are from Paul Celan’s Todesfugue; the loss of Sulamith is a symbol of the Holocaust. Political reunification in 1990 restored the former east, but the real ‘other half’ of German history, the Jewish part, could never be restored.

Kiefer’s range of subject matter and references is epic. Since the 1980s overtly Germanic themes – the forest, the Nibelungen, the Third Reich – have been joined by Mesopotamian history, Egyptian and Greek mythology, the Old Norse Edda and the Kabbalah. A summary of these interests is captured by The Rhine, an installation of monumental woodcuts displayed on free-standing screens: Goethe, Dürer, fascist architecture, the poetry of Celan, all hovering above an image of the longest German river. It is a testament to Kiefer’s tact that, despite the grandiosity of these themes, his work never feels overblown. At the heart of the Royal Academy display is an installation, Ages of the World, a title loosely translated from the German Erdzeitalter. A lofty, tapering stack of discarded canvases, stretched and rolled, interleaved with old photographs, rubble, lead books and more large dried sunflowers gives off a faint odour of the dust and solvent of an artist’s studio. Two works on the wall, large photographs of the sculpture overpainted with words, annotate the stack in terms of the strata of geological eras. At first it seems to be a monument to art’s failure in the face of history, or an attempt to escape history. The critic John Russell saw an earlier form of the work, titled Twenty Years of Solitude (1971-91) as a ‘portrait of the artist as Atlas, bearing upon his shoulders a whole world in epitome’. But despite this the mood remains somehow light, as though a burden has been shifted, a knot unravelled.

This (relative) lightness of mood is one of the most striking qualities of Kiefer’s monumental works. These have taken the form of vast crumbling concrete towers, libraries of lead books – or the two enormous studio complexes he runs in France (descriptions of visits to these studios to interview the artist are a sub-genre of the Kiefer literature). The effect can be seen in the large canvas For Ingeborg Bachmann: The Sand from the Urns, 1998-2009 (even the date range is epic) which shows a large brick structure, perhaps a tomb, barely visible beneath a surface of acrylic and shellac (who knows what else might be lurking in there), the whole thing encrusted in a thick layer of sand. The title refers to the two poets whom Kiefer holds in greatest reverence; when Celan embarked on an ill-fated affair with Bachmann, he inscribed his poem ‘In Egypt’ in his collection The Sand from the Urns for her: ‘Thou shalt say to the strange woman’s eye: be the water!’ The surface of the painting recalls Joyce – ‘These heavy sands are language tide and wind have silted here’ – but at the same time his citation from Celan counters the heaviness of the lead books, the pyramids, the halls of fame, with a dash of mysticism to suggest that there is something to be read in those leaden tomes after all. His schoolbook-like script (which strongly recalls the lettering Kitaj used on his paintings) adds to the sense of more simple histories and truths, and also reveals something of Kiefer’s sense of humour, which he has sustained since the absurdist satire of the Occupations photographs. An endearing crankiness helps his work to survive the grandiosity of its subject matter.

As a retrospective the Royal Academy show is far from definitive. A weighting in favour of recent works, including two large diamond-encrusted lead-sheet ‘paintings’, and a room of seven new paintings, characterised by their rich gilded surfaces and grouped under the title Morgenthau, gives the impression of a mid-career show, organised in a commercial rather than a scholarly context (although the catalogue is highly informative and contains a fine essay by Christian Weikop on Kiefer’s use of tree and forest symbolism). It offers an opportunity to marvel, but not to get beneath the skin of Kiefer’s work, or to see him alongside other artists. His considerable debt to Joseph Beuys, at one time his teacher, is a case in point. The dried roses Beuys stuffed in a piano in 1969 are surely the origins of Kiefer’s sunflowers; and where Beuys used felt and fat as his signature materials, Kiefer uses lead (salvaged, we are told, from the roof of Cologne cathedral). The use of inscriptions, and the sense that an attempt is being made to create allegories of recent history also joins the two artists, although there are many differences too: Beuys was not a painter, for example; and Kiefer, since hisOccupations photographs, is not known for performances. And in many respects Kiefer has gone beyond his former teacher in creating a body of work that captures the experience and memories of a German artist working in the wake of the Third Reich. But it isn’t his subject matter, or even its poetic transformation, that makes Kiefer’s work so beguiling, particularly when compared with that of artists such as Beuys or Georg Baselitz. It is something far more prosaic: the fascination of running one’s eyes over the intricate surfaces of his paintings, admiring the sense of design in his woodcuts, his skill in painting in watercolour, or ingenuity in recycling materials for sculpture – the pleasure of wondering how it was all done.

=====

Anselm Kiefer review – remembrance amid the ruins

Royal Academy, London

Anselm Kiefer’s monumental work in ash, straw, diamonds and sunflowers dazzles in a superb retrospective

Anyone who knows even the smallest thing about Anselm Kiefer will have gathered that his ambitions are not ordinary. An old-school history painter, didactic and inescapably moral, he works on a grand scale in lead, sand, gold leaf, copper wire, broken ceramics, straw, wood and even diamonds, his ideas informed by, among many other subjects, the Holocaust, Egyptian mythology, the architecture of Albert Speer, German Romanticism and the poems of Paul Celan. He is the kind of artist whose physical presence – in his black T-shirts and rimless spectacles, he puts one in mind just lately of an executive from Apple – always comes as a surprise. How, you wonder, can a man who deals with so much weighty stuff have such regular-looking shoulders, such ordinary biceps? And why is he smiling? Doesn’t the darkness ever threaten to engulf him? Doesn’t his project – now more than 40 years old – sometimes pinch at his sanity?

Yet only with the help of a blindfold would you be able to wander the Royal Academy’s stupendous retrospective of his work and leave feeling anything less than drunk with amazement. However much you know about Kiefer, it’s impossible to be prepared for this show: for its scale, its pleasures, its provocations and – this must be said – its bafflements. This is a total experience. The work first speaks to the eyes, which instinctively scour every last corner of every painting, every sculpture. Then it calls to the heart, pulling from you all sorts of things Kiefer certainly didn’t intend (in my case: modern-day Syria; the 80s nuclear TV drama Threads; John Wyndham’s novel The Day of the Triffids). Last of all, it engages the head, as you attempt to unravel his complex, multilayered narratives. It’s certainly useful to know your history before you enter these spaces – and if you’re fluent in the language of Richard Wagner and Caspar David Friedrich, so much the better. But it isn’t necessary. In any case, mystification is half the point. No artist puts this much effort into the construction of their work without wanting their audience to linger over it, to try and fathom it out.

Kiefer was born in the Black Forest in 1945, a kind of year zero in terms of German history. And it’s this – the attempt to wipe out collective memory after the war – that has long been his creative wellspring (at school his teachers hardly mentioned the Third Reich). Taught by Joseph Beuys, the artist who helped Kiefer’s generation to reclaim much of the historical and mythological imagery rendered so toxic by the Nazis, his early work depicts himself, dressed in his father’s army uniform, taking the Nazi salute outside the Colosseum in Rome and elsewhere. The Royal Academy show, which works chronologically, begins with this zesty, youthful reappropriation. I was queasily hypnotised by the watercolour Ice and Blood (1971), in which an expanse of snow is scarred with pools of crimson and, far worse, a tiny, naive figure in a military overcoat, its right arm ominously raised. Before you get there, though, the Royal Academy reveals its breathtaking commitment to Kiefer with a little reappropriation of its own. The garish shop at the top of the gallery’s stairs has disappeared. In its stead is Language of the Birds (2013), a monumental sculpture comprising a pile of charred-looking books with a huge set of wings attached. Do these belong to a German eagle? Naturally, that’s what comes to mind. But I kept thinking, too, of the phoenix, a creature that speaks to Anselm’s preoccupation with myth, rebirth and the cycles of time every bit as loudly as the Reichsadler.

The phoenix rises from the ashes, and this, after all, is a show that is covered in clinker. Ash Flower (1983-97), made of oil, acrylic, paint, clay, earth, ash and – a recurring symbol in Kiefer’s work – a dried sunflower, is a seven metre-wide depiction of a ruin, the ruthless lines of a grand public building emerging through its murky surface like the prow of a ship through fog. Sulamith (1983), inspired by a Paul Celan poem, Death Fugue, which was written in a concentration camp (“your ashen hair Shulamite”), is a gloomy crypt rendered in oil, acrylic, woodcut, emulsion and straw, at one end of which a fire endlessly flickers. Untitled (2006-08) consists of a triptych of huge vitrines in which there resides a wintry graveyard of brambles, dead roses, more ash, and toppling concrete houses. Gradually, the work starts to talk to the future as well as the past. In the Royal Academy’s octagonal gallery is a new piece, Ages of the World (2014): a pile of abandoned canvases and rubble bedecked with an unhappy coronet of yet more dead sunflowers. It has a dystopian, post-apocalyptic feel: no culture, no hope.

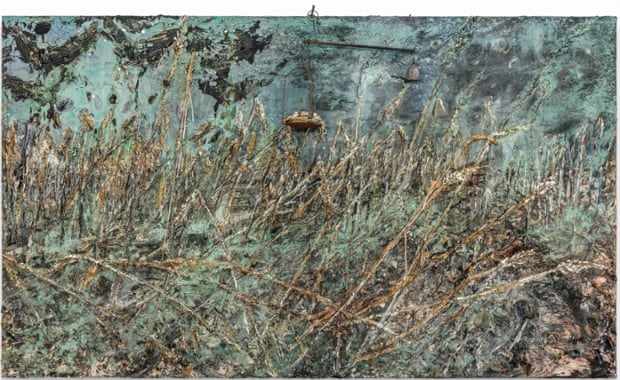

All this is pitch-dark. But there is radiance elsewhere – and colour too. For Ingeborg Bachmann: the Sand from the Urns (1998-2009) is a depiction of a ziggurat in a sandstorm so astonishingly dynamic you’re almost tempted to squint, the better to protect your eyes, while the satirical Operation Sea Lion(1975) has toy battleships floating in one of the zinc baths that were given to every German home by the health-obsessed Third Reich, its water a horribly chipper shade of blue. Best of all there are Kiefer’s Morgenthau paintings from 2013, named for the US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jnr – whose plan it was in 1944 to transform Germany into a pre-industrial nation as a means of limiting her ability to fight future wars – and crammed with impasto stalks of corn that sometimes blow and bend, and sometimes reach for the blazing sky. A note on the wall urges the visitor to note the crows circling above, a symbol of death and resurrection. But it isn’t these flapping shadows that keep you in the room; it’s the whispering grass, the beatific sunshine, the splashes of cornflower blue. Kiefer is that most resolute of artists. He has never turned away from the difficult and the sombre; his career is a magnificent reproach to those who think art can’t deal with the big subjects, with history, memory and genocide. In the end, though, what stays with you is the feeling – overwhelming at times – that he is always making his way carefully towards the light.

===

FINANCIAL TIMES LONDON

September 19, 2014 6:38 pm

Interview with Anselm Kiefer, ahead of his Royal Academy show

©Howard Sooley

©Howard Sooley

Anselm Kiefer in front of his work ‘Ages of the World’ (2014)

When I tell Anselm Kiefer that my favourite work in his forthcoming Royal Academy retrospective is “Tándaradei” – a monumental new painting in oil, emulsion and shellac where pink, red and mauve blossoms seem to burst into life, fade, wilt, all at once – the artist looks apologetic. “I put it out of the exhibition because it’s too beautiful. It’s too much. I couldn’t allow it.”

Painters have been quarrelling about beauty for centuries but Kiefer, born in southern Germany in the last months of the second world war, has rooted his life’s work in the urgent postwar anxiety about art’s role and future: Theodor Adorno’s claim that there could be no poetry after Auschwitz.

“You cannot avoid beauty in a work of art,” says Kiefer. He waves at a room full of richly textured works with scorched, barbed surfaces – built up from ash, lead, shards of pottery, battered books and broken machines – that evoke war-ravaged wastelands but have lyricism etched into the violence of their making. “You can take the most terrible subject and automatically it becomes beautiful. What is sure is that I could never do art about Auschwitz. It is impossible because the subject is too big.”

This is a conversation stopper because Kiefer has rarely made art about anything else. In the 1960s he made his debut as a performance artist: dressed in his father’s army uniform, he photographed himself making the Nazi salute in iconic European locations such as Rome’s Colosseum, confronting what his fellow artist Joseph Beuys called Germany’s “visual amnesia” about the Holocaust. Half a century later, at this year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy, he displayed a new painting “Kranke Kunst” (“Sick Art”), a lovely willowy reprise of a 1974 watercolour of the same name in which a landscape of the kind idealised by the Nazis was dotted with pink boils.

Kiefer explains: “I like the double sense, first ‘Kranke Kunst’ is negative, it comes from Nazi censorship of entartete Kunst [degenerate art]. And then, it’s completely true because all is ill, the situation in the world is ill . . . Syria, Nigeria, Russia. Our head is generally ill, we are constructed wrong.”

What can art do?

“Art cannot help directly. Art is the way to make it obvious. Art is cynical, it shows the negativity of the world, it’s the first condemnation.”

Can art be celebratory?

“Matisse, he celebrates, but I see through this – to desperation.”

Kiefer says all this to me cheerfully, deadpan, over vodka at three in the afternoon in his 30,000 sq metre Paris atelier, a former warehouse of the department store Samaritaine. Another studio in Barjac, southern France, occupies a 200-acre estate but even the Paris one is so extensive that you need a car to cross it, past rusting tanks, containers with paintings left out to the chance elements of weather, and rose bushes planted by the artist. At one point we nearly collide with a crane hoisting a slab of lead. “For me, huge doesn’t exist,” Kiefer admits.

. . .

Tall and greying but lean and swift in white shorts and open shirt, the 69-year-old has fled preparations for the show in London – “It’s boring for an artist to do a retrospective” – but he offers a tour of the work here. Sculptures wrought from damaged bomber planes are strewn across one studio. Styrofoam towers from his nine-storey set for the Bastille Opera’s In the Beginning tumble and crumble in another. Hundreds of bleached-out resin sunflowers at three times life size, a comic homage to Van Gogh, stand guard at the gated entrance.

You cannot avoid beauty in a work of art

Sunflowers like these are coming to London, part of an installation, entitled “Ages of the World”, of unfinished canvases stacked horizontally into giant rubbish heaps that will occupy the RA’s opening central hall. I had interpreted an allusion to German history, the unhealable rupture imposed by the Nazi attack on degenerate art. Kiefer, however, points to monochrome gouaches that will surround his fallen canvases, which are scrawled with words referencing stratigraphy, palaeography, geology.

“Archaikum, mesozoikum,” he recites, drawing out the syllables like a line of poetry. He speaks English well but relaxes into real pleasure of expression when lapsing into German. “I like these words! How many million years are we old? You don’t know? You don’t know our age! I have all this catastrophe in my biography. That is what you see in ‘Ages of the World’. We go back much before our birthday. In our mind is inserted all this stratigraphy. Three hundred and fifty million years ago a meteorite touched the earth and 95 per cent of life was extinguished. Three hundred and fifty million years ago the dinosaurs – and lots of people – died. German history? It starts with Archaikum.”

In one of the most affecting paintings in the exhibition, “The Orders of the Night” (1996), there are also giant sunflowers, blackened, lined up in rows, menacing as soldiers, looming over a self-portrait of Kiefer as a corpse. And dried sunflowers mix with ash, clay and oil in the sombre, tapering interior, “The Ash Flower” (1983-87), the show’s largest painting at nearly 26ft wide.

At the Royal Academy, such ghostly interiors, echoing with references to Hitler’s architect Albert Speer, such as the chancellery in “To the Unknown Painter” (1983), will hang alongside desolate versions of the forests and fields of the German romantic imagination: landscape destroyed in “Painting of the Scorched Earth” (1974); deathly in the shimmering straw of “Margarethe” (1981), representing the blond camp guard; paired with the dark straw ashes of the victim of the furnaces “Sulamith” (1983); or inscribed with the poems of Paul Celan and studded with charred books in the more recent furrowed “Black Flakes” (2006).

When I got an early glimpse of the show, these struck me as the dark heart of Kiefer’s achievement I ask him if he feels that these were the works he inevitably had to make. “No, no. Perhaps I should have been a poet or a writer. You can never be sure because you make mistakes but the mistake becomes reality.” Poems, he says, “are like buoys in the sea. I swim from one to the next; in between, without them, I am lost.” He says Celan, a Holocaust survivor, “is the most important poet since the war. He puts words together as no one did before. He made another language, he’s an alchemist concerning words.”

Is alchemy a metaphor for what Kiefer does? “It is what I do,” he corrects. “Alchemy is not to make gold, the real alchemist is not interested in material things but in transubstantiation, in transforming the spirit. It’s a spiritual thing more than a material thing. An alchemist puts the phenomena of the world in another context. My bird is about that . . . ” He points out “The Language of Birds”, a new avian sculpture whose body is composed of burnt books, also to be completed for the London show. “It’s made with lead and strips of silver, gold. Its wings are lead and can’t fly, the books can’t fly, the metal is solid, but it changes.” He loves lead because “it has always been a material for ideas. It is in flux, it’s changeable and has the potential to achieve a higher state.” He grins: “And then, my paintings have a certain value, so I’m an alchemist.”

Art cannot help directly. Art is the way to make it obvious. Art is cynical, it shows the negativity of the world, it’s the first condemnation

Kiefer’s auction record is $3.6m, achieved for “To the Unknown Painter” in 2011, and he is represented by blue-chip dealers Gagosian, White Cube and Thaddaeus Ropac; indeed, in 2012, both Gagosian and Ropac launched massive galleries in Paris with rival Kiefer shows, flaming criticism of overproduction and repetition. “Kiefer has become better and better at making Anselm Kiefers. In them grandiosity rarely takes a holiday,” wrote Roberta Smith in The New York Times of a 2010 Gagosian Manhattan show. In that exhibition, Next Year in Jerusalem, Kiefer’s references to Jewish mysticism and history, a strand in his work since the 1980s, attracted protesters against Israel’s blockade of Gaza; wearing T-shirts inscribed with the show’s title, they asked to stay in the gallery to continue discussions raised by Kiefer’s work. The gallery called the police, saying, “This is private property. We’re here to sell art.”

Was this a betrayal of Kiefer’s seriousness, an admission that 21st-century art is primarily a commodity? I can think of no other contemporary figure who operates at the interface of art, money, politics and history as prominently, and with such confident equilibrium, as Kiefer. It is undeniable, and borne out by unpredictable auction results, that the quality of his prolific output is uneven, sometimes top-heavy with portentous theme or occult narrative. On the other hand, the cohesion of ideas and tone in the RA show, Kiefer’s first retrospective, dramatises how the conceptual impetus underpinning his material endeavours mean that all his works belong together as a sort of Gesamtkunstwerk – or even as a performance piece in progress, which began with his solitary Sieg Heil in Rome half a century ago.

At his Wagnerian stretch, Kiefer is a very German artist, though he left the country in 1990, after reunification. He says: “Since I live in France it seems that I am more German. Thomas Mann wrote Buddenbrooks in Rome: when he was in Italy he became aware of being German. It’s clear that I am in the tradition of German art, Holbein, Dürer, Caspar David Friedrich, but national character is no longer so present. The last time there was real distinction between French and German art was impressionism, which was French, and expressionism, which was German – then it was clear who was who. Now it’s not global but it’s European – if I take America as part of Europe, though they will not like that! In America and the UK it’s about the work. In Germany it’s always linked to some moral issue.”

It seems to me that there are two things that make the Royal Academy show significant beyond an account of one man’s vision. This autumn Kiefer is being shown alongside two German near-contemporaries, Sigmar Polke at Tate Modern and Gerhard Richter at Marian Goodman’s new Mayfair space. Each came of age in a morally fatherless culture and had to negotiate positions vis-à-vis German history: Polke’s was fundamentally absurdist, Richter’s ironic, and Kiefer’s is broadly tragic. All are valid responses to Adorno.

But an RA show is also an institution boasting a centuries-old history of debate about the formal nature of painting. Kiefer follows exhibitions devoted to Anish Kapoor, who in 2009 drove a “paint train” through the galleries and shot pigment at the walls from a gun; and to David Hockney, who in 2012 challenged traditional painting with iPad sketches enlarged to enormous scale and film. Both artists proved that painting could rival younger media as spectacle, theatre, performance; this show will do the same.

Before I leave Paris, Kiefer shows me a group of green-gold paintings, encrusted with metal, polystyrene, shellac, sheaves of wheat, paint layered over photographs, a shoe, a pair of scales. This is the Morgenthau series, begun in 2012 and named after a leaked, abandoned wartime American plan to deindustrialise Germany. “A big present to Hitler,” says Kiefer, “because he was able to say, ‘If you don’t fight, this will happen to you. Fifty million Germans would have died – though that’s nothing [compared] to Mao.”

I could never do art about Auschwitz. It is impossible because the subject is too big

Kiefer has made some new Morgenthau paintings especially for Burlington House. Altogether there are a lot of them: an obvious glitzy currency for a widening collector base. They are also rather beautiful.

“I came to the title,” Kiefer explains, “because I so much like flowers and I painted so many flower pictures that I had a very bad conscience, because nature is not inviolate, nature is not just itself. So what to do with this beauty? I thought, ‘I will call it Morgenthau’, in a cynical way telling that Germany would be so beautiful without industry. This way of turning it round, it tells you the ambiguity of beauty.”

A smart conceptualist’s marketing strategy or an artist making peace with the tradition of painting? Kiefer pauses to marvel at an emerald hue while fingering the gold leaf, which he has layered on to sediment of electrolysis, an industrial galvanisation process to which he submits the works – a modern alchemy. “You cannot produce it, it’s such a powerful green, that’s the electrolysis, it changes the painting and when I see it, I am surprised. And that’s what I live for: to be surprised.”

‘Anselm Kiefer’ is at the Royal Academy, London, September 27 to December 14, royalacademy.org.uk

Jackie Wullschlager is the FT’s chief visual arts critic. Read her review of Constable at the V&A

Photograph: Howard Sooley

==