http://www.domusweb.it/en/reviews/2006/12/04/szeemann-s-work.html

![]()

Szeemann’s work

from Domus 898 December 2006

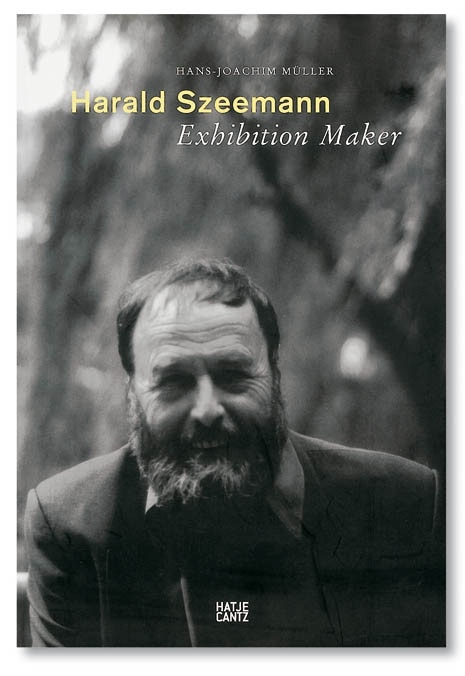

Harald Szeemann. Exhibition Maker, Hans-Joachim Müller, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany 2006 (pp. 168, s.i.p.)

Harald Szeemann reformed curatorial practice. Müller’s book leads us along the great Swiss critic’s intellectual path via his exhibitions.

Harald Szeemann. Exhibition Maker, Hans-Joachim Müller, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany 2006 (pp. 168, s.i.p.)

Harald Szeemann reformed curatorial practice, a job that had been seen in museums for 200 years and was equated with that of the conservator, Alfred Barr having been the leading example for modern art. Müller’s book leads us along the great Swiss critic’s intellectual path via his exhibitions.

Harald managed to grasp certain aspects of contemporary art and create a far more versatile and mobile figure of the “critic” in the modern tradition. One who follows, interprets and defends artists’ projects when they are treading on experimental terrain without knowing exactly which direction they will take. His close bond with the artists of the 1968 generation, which can be epitomised with the names of Joseph Beuys, Mario Merz, Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra – the galaxy of reference for his entire lifetime – helped him create the condition of the independent curator. The person who is able to conduct a relationship with artists as a mediator and communicates with all the other art-world structures and the greater public.

However, he was not only a mediator of the art world. He was also a great interpreter thanks to a visionary capacity that distinguished him from all others, adversaries and imitators alike. He did not see the problem of curating exhibitions as a simple operational matter linked to the practice of organising. Harald had the ability to condense the symbolic force of a work or an object within the exhibition space, constructing exhibitions that were great productions of fantasy: visions of a specific epoch – the art of the second half of the 1960s – but also of a community or a geographic area. He always rejected the concept that art was simply an expression of formal values, the direction in which the art market and museums drove it for structural reasons.

In his work as a curator he managed to create a critical space that was independent of the other art institutions. This is also why he curated many apparently thematic exhibitions in his lifetime that seemed to have little or nothing to do with the artistic debate in course, such as the “Monte Verità” exhibition on the utopian community of Ascona, that on the concept of the total work of art “Der hang zum Gesamptkunstwerk”, and the “visionary” Switzerland, Austria, Belgium series and the “Money and Value” pavilion at the 2002 Swiss exhibition.

It was a method that allowed him to interpret his own times. These were flanked by exhibitions that had a profound impact on the contemporary art debate and changed the course of the history of art, such as “When Attitudes Become Form” and “Documenta 5”, which were followed by the no less important “Machines celibataires” and “Aperto 1980” at the Venice Biennale, plus the more recent ones he curated himself at the 1999 and 2001 Venice biennials.

In his exhibitions Harald always tried to pinpoint the conceptual density of the materials and he had an elevated idea of the avant-garde, able to show the world a different approach to the reality of art. In his work, he always tried to lend substance to artists’ visions and their ability to produce “personal mythologies” as he called them. The exhibitions often became visual routes, created using the artists’ works and objects of strong symbolic worth that were sometimes confused one with the other because of the everyday provenance of both. The aim, however, was always to conceive the exhibition as an autonomous space, a sort of social interstice in which to reconstruct a critical area that reacted to the secularisation of the world. In this sense, he was strongly influenced by the work of Joseph Beuys, at least from the 1970s on. As Müller wrote: “Szeemann thought he was the ‘most important artist since World War II.’ His faith in the (…) social and anthropological responsibility of the aesthetic paradigm and the vital reinforcement of visions was the strongest reflection for those utopias to which Szeemann’s exhibitions tried to lend substance.” (p. 108) The misinterpretations of his work by curators of the 1980s, who wanted to retrieve the European cultural substratum as a reaction to the standardisation and “Americanisation” of the world, were a direct consequence of this attitude.

Harald, however, understood how much the communication dimension had influenced art in the 1990s and with the ideas of “everywhere”, “open” and “audience of humanity” the two biennials of Venice clearly showed how hard he had tried to interpret that element of newness, sometimes with peaks of spectacularisation that were bound to the moment and managed to relaunch the Venetian institution in crisis. If today’s exhibitions have become common critical tools in the artistic debate – albeit often minus the conceptual density that his possessed – we owe much of it to him and are all indebted to him. If I think hard, I can still see his black Mercedes driving into the street for our last appointment in front of his office in Valle Maggia: the great Szeemann will be sorely missed.

Maurizio Bortolotti, Art critic

==

The show that made Harald Szeemann a star

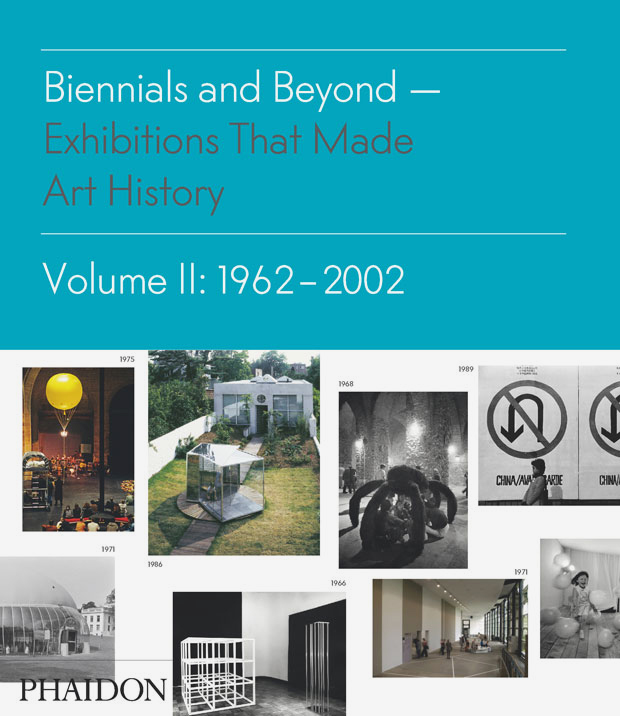

Biennials and Beyond looks at the exhibitions, curators and artist run spaces that helped make art history

Harald Szeemann, curator of Live In Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form: Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information

One of the things we love about art is its capacity to ruffle feathers. Maybe it’s the unresolved punk rocker in us at phaidon.com but the mockery, vituperation – not to mention the occasional dumping of manure outside a gallery entrance – that has accompanied some groundbreaking art shows over the years is all grist to our mill. Which is why we’ve spent the last week ensconced in Biennials and Beyond – Exhibitions That Made Art History 1962-2002, a new book that takes an in depth look at the shows that really did change the course of art.

Last night we were poring over the section dedicated to Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, the show held at Kunstalle Bern in the spring of 1969. It was remarkable for a number of reasons not least because in Harald Szeemann, it introduced us to the idea of the curator as we know it today. Here’s a little extract from the book which will explain more.

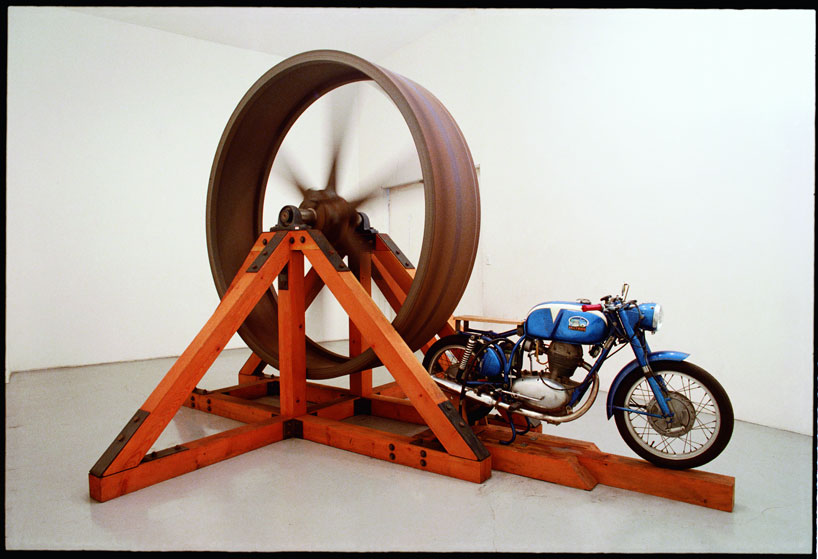

Belt Piece – Richard Serra

As both foundational event and conceptual model, “When Attitudes Become Form” holds a special place in the curatorial imagination. It was the exhibition that brought international acclaim to the most important curator of the post-war period, Harald Szeemann. And it was the show that led Szeemann to re-create himself as an independent exhibition maker, founding a career path that would be followed by generations of curators. “Attitudes” has also come to represent the romantic conception of the curator as inspired partner of the artist, a creative actor who generates original ideas and structures through which art enters public consciousness.

Szeemann was an advocate for the new art that emerged in the 1960s, work grounded in an “inner attitude” elevating artistic prcess over final product. Across the diversity of Conceptualism, land art, American Post-Minimalism, and Italian Arte Povera, he also experienced a desire to be free of a system supplying aesthetic objects for the wealthy. He displayed this attitude and this aspiration by turning the Kunstahlle Bern into a giant artist’s studio, accommodating the practical demands of process -based art through Piero Gilardi’s idea of the exhibition as workshop and locus of discussion.

Capturing the ethos of the 1960s, Keith Sonnier contributed the phrase atop the catalogue page “Live In Your Head”. The catalogue alluded to Szeemann’sprcess as well as to that of the artists, containing the address list he used in New York and letters responding to his invitations to exhibit.

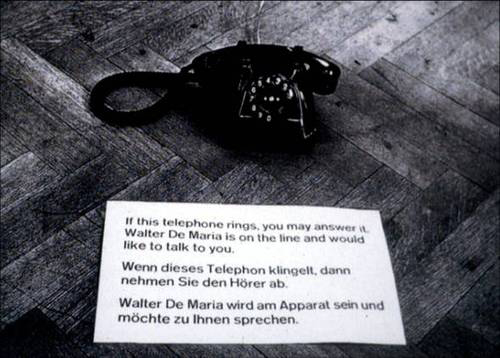

Art By Telephone – Walter de Maria

The book then goes into fascinating detail regarding the show. Richard Serra splashed lead inside the Kunsthalle foyer, Jan Dibbets excavated a corner of the building to expose their foundations. Michael Heizer smashed the sidewalk outside the museum while Daniel Buren pasted his signature stripes around the town and was promptly arrested for his trouble. Illegality was compounded with the burning of military uniforms outside the museum, which wasn’t part of the show but was associated by the public with it.

The conservative Swiss public did not react well to the show. There was mockery in cartoons and manure, was indeed dumped at the entrace to the Kunsthalle. Despite positive reviews the museum cancelled Szeemann’s planned Joseph Beuys show. He resigned as director and the rest, as they say, became history.

Check out the book in the store, it really is packed full of fascinating stories and insights into the shows of the time and it’s fast becoming our go to read here at phaidon.com, filling in any gaps in our art history knowledge in an innovative but easy going way. It’s also particularly good on the role of commercial galleries, the influence of museums and corporate groups and the impact of globalisation on the art world.

Biennials and Beyond – Exhibitions That Made Art History

==

http://frieze.com/issue/article/harald_szeemann_1933_2005/

Harald Szeemann 1933 – 2005

ICONS

Remembering the life and work of one of the most influential and imaginative curators of the last century

![image]()

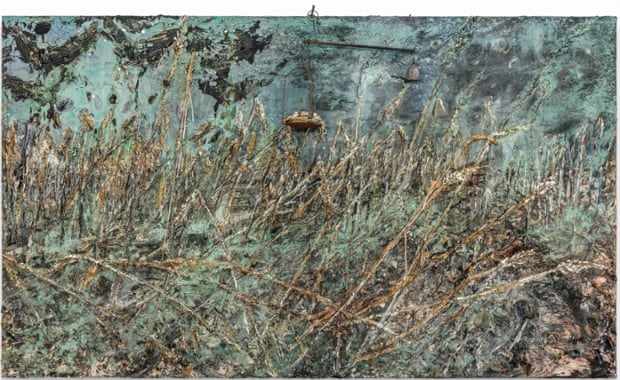

Richard Serra

For me, since 9/11, there has been a daily ritual commemoration of the dead. I seem to be surrounded by death. Everything seems to make forgetting impossible. There is a growing voyeuristic detailed description of the terror of death via the media; and the more I consume, the less I grasp. Death as an incomprehensible phenomenon has produced a certain numbness in me and then I am told that a friend of mine for over 30 years has died and I am asked to write a few words. Writing is one form to seek compensation for loss. Death is an all too human fact. You don’t only live out your life, you also live out the lives of your contemporaries. Their mortality affects your living, your daily measure.

Harry was a great man who supported art and artists unequivocally his entire life. For decades he was able to pull forth meaning where others would only find absence – that is, he gave all artists the benefit of the doubt. The last time I was with Harry I laughed so hard I cried and that is the way I want to remember him.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

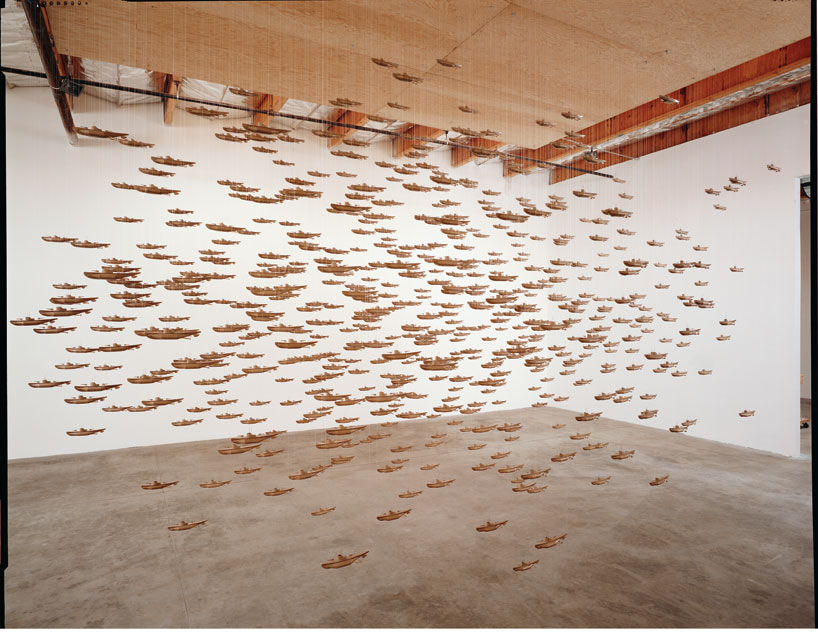

The curatorial work of Harald Szeemann was highly complex and cannot be seen as having just a single aspect. For me his exhibitions in Zurich – and above all Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk (The Tendency towards the Total Work of Art, 1983), which I visited every day while still at school – were formative experiences. This was due in part to Szeemann’s notion of the exhibition as a toolbox, as an archaeology of knowledge in the spirit of Michel Foucault. Whether he was showing Artaud, Gaudí, Schwitters, Steiner or contemporary artists, Szeemann accomplished the rare feat of bridging the gap between past and present. He tested out so many different modes of exhibiting, as well as curating many important solo shows: Beuys, Delacroix, De Maria, Duchamp, Merz, Nauman, Picabia, Serra … The 1985 Mario Merz exhibition, in particular, made a particularly lasting impression: Merz and Szeemann removed all the walls inside the Kunsthaus and displayed the work as an open field, with Merz’ igloos shown in the resulting space as a visionary and Utopian city: La Città Irreale.

Szeemann also saw his exhibitions as an ‘archive in transformation’. To me this was just as representative of his approach as the fact that he worked simultaneously as an independent curator and curator of Kunsthaus Zürich. Another important facet of his career was the way he oscillated between large and small, private and public. After the 1972 Documenta in Kassel, for example, there was the exhibition dedicated to his grandfather, held in a private apartment in Bern, with no hierarchy between the larger and the smaller show – entirely in keeping with Robert Musil’s observation that art can appear where one is least expecting it. Szeemann’s death is a major blow to the art world.

Visionary Belgium by Aaron Schuster

A mescaline-minded poet (Henri Michaux), the self-styled commissar of a bankrupt museum (Marcel Broodthaers), a bungling megalomaniac raised by a Belgian boulangerie owner and a web-footed French prostitute (Dr Evil in Austin Powers), an amateur scientist in tireless pursuit of the Absolute (Honoré de Balzac’s portrait of the Fleming Balthazar Claes) – Belgium, a country of visionaries? Such was the explicit wager of Harald Szeemann in his sprawling show, La Belgique visionnaire. C’est arrivé près de chez nous (Visionary Belgium. It’s in your neighbourhood) on display until mid-May, 2005 in the Victor Horta designed Palais des Beaux Arts. The late curator liked to refer to his method as one of ‘structured chaos’, and that is precisely what is presented here: a highly varied collection of paintings, advertisements, films, sculptures, books, archival materials and installations without any discernible organizing principle except to reveal that elusive quality known since the late 1970s as la belgitude.

The first thing to mention apropos this exhibition is Szeemann’s brilliant insight into which countries constitute the visionary core of Europe – the repository of its utopian longings, twisted dreams and undialectizable contradictions. ‘Visionary Belgium’ is the last in the sequence of three exhibitions, beginning with ‘Visionary Switzerland’ (1991) and followed by ‘Austria im Rosennetz’ (Austria in the Net of Roses, 1996). Here Szeemann’s intuition was spot on: one simply cannot imagine the same treatment of ‘major’ European nations like Germany, France and, in spite of its eccentricities, England, or even Spain or Italy. Visionary potential must rather be sought in the margins of the margins, in the dissident traditions within those countries that already have a ‘minor’ status. In this respect, one should also mention the Balkans, to which Szeemann consecrated the show ‘Blood and Honey’ in 2003. If the title of this latter exhibition cannot help but conjure up clichéd images of irrational violence on the one hand and the poetry of everyday rustic life on the other, this would seem to point to a more general difficulty implicit in the curator’s method. To borrow a term dear to him, this method might be dubbed ‘pataphysical anthropology’: an attempt to discern the ‘spiritual contours’ of a region via an examination of its most extraordinary and even unclassifiable cultural artifacts. As Szeemann understood, such an enterprise is not without dangers, and ‘Visionary Belgium’ sometimes risks becoming a mere ‘cabinet of curiosities’, reproducing the stereotype of Belgians as a darkly quirky, self-deprecating people. To voice another concern: the show also seems more backward than forward-looking, more retrospective in its approach than interested in divining what (if anything) is new and exciting in the Belgian scene.

These critical suspicions aside, ‘Visionary Belgium’ is an extremely rich exhibition. Apart from collecting together works of famous artists like René Magritte, Léon Spilliaert, Paul Delvaux, Félicien Rops, and Broodthaers, and contemporary stars such as Panamarenko and Wim Delvoye (a new upright version of the shit-machine Cloaca 2005), the main merit of the show lies in its unearthing of lesser known figures and events. To mention just a few: an extensive documentation of the avant-garde festival EXPRMNTL held each winter at the seaside resort Knokke from 1949 to 1974; the space reserved for pataphysician André Blavier’s personal library, including Professor Dewulf’s 1950s Debraining Machine; and, a large card catalogue transported from the archives of the Mundaneum in Mons, Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine’s early 20th-century utopian project to gather together all human knowledge. Benoît Poelvoorde’s C’est arrivé près de chez nous (1992), an exceedingly noir exercise in black humour, provides the show with its appropriate subtitle though it could have equally been named ‘The major ordeals of Belgium and the countless minor ones’ – a variation on the title of one of Michaux’s drug-inspired books. That major ordeal is none other than the strained existence of the Belgian state itself, a theme that resonates in many of the displayed works. Though the exhibition takes place within the rubric of Belgium’s 175th anniversary celebrations, it is significant that the country cannot commemorate this event without adding ‘and 25 years of federalism’, which is tantamount to simultaneously celebrating one’s birthday and divorce. Indeed, one could argue that the key to both Belgium’s visionary culture and its reactionary politics is precisely its lack of a well-defined centre or strong sense of national identity. It is therefore fitting that what ought to have the centrepiece of the exhibition, James Ensor’s The Entry of Christ into Brussels (1888) is missing; evidently Christ took a wrong turn somewhere and ended up in Los Angeles (the painting is in the Getty Museum). The absence of this remarkable work, mixing Christian theology with the International, in turn echoes another, more fundamental loss: the demolition of Horta’s La Maison du Peuple in 1954 – Brussels’s lost object of desire. It would hardly be a stretch to surmise that it is the populist socialist vision condensed by these two missing works – the breaking up of the dream of social fraternity – that provides the ultimate backdrop for the multiple visions of Belgium.

Szeemann is perhaps the single figure most responsible for the image we have of the curator today: the curator-as-artist, a roaming, freelance designer of exhibitions, or in his own witty formulation, a ‘spiritual guest worker.’ In a way this shift in the role of the curator makes perfect sense. If artists since Marcel Duchamp have affirmed selection and arrangement as legitimate artistic strategies, was it not simply a matter of time before curatorial practice – itself defined by selection and arrangement – would come to be seen as an art that operates on the field of art itself? Daniel Buren first voiced the critique of this development against Szeemann’s curatorship of Documenta 5 in 1972, and since then the polemic has only gained in intensity. Rather than repeating the same stale scripts, however, what would be useful today, and to my knowledge has yet to be written, is a critical history of curating, a study of the transformations in the manner of art’s staging and public presentation.1 It goes without saying that in such a study Szeemann would figure as one of the grand innovators.

Richard Serra and Hans Ulrich Obrist

=====

THE BROOKLYN RAIL

The Bias of the World: Curating After Szeemann & Hopps

by David Levi Strauss

What Is a Curator?Under the Roman Empire the title of curator (“caretaker”) was given to officials in charge of various departments of public works: sanitation, transportation, policing. The curatores annonae were in charge of the public supplies of oil and corn. The curatores regionum were responsible for maintaining order in the 14 regions of Rome. And the curatores aquarum took care of the aqueducts. In the Middle Ages, the role of the curator shifted to the ecclesiastical, as clergy having a spiritual cure or charge. So one could say that the split within curating—between the management and control of public works (law) and the cure of souls (faith)—was there from the beginning. Curators have always been a curious mixture of bureaucrat and priest.

That smooth-faced gentleman, tickling Commodity, Commodity, the bias of the world—

—Shakespeare, King John1

![]() Portrait of Harald Szeemann. Pencil and Paper by Phong Bui.

Portrait of Harald Szeemann. Pencil and Paper by Phong Bui.For better or worse, curators of contemporary art have become, especially in the last 10 years, the principal representatives of some of our most persistent questions and confusions about the social role of art. Is art a force for change and renewal, or is it a commodity for advantage or convenience? Is art a radical activity, undermining social conventions, or is it a diverting entertainment for the wealthy? Are artists the antennae of the human race, or are they spoiled children with delusions of grandeur (in Roman law, a curator could also be the appointed caretaker or guardian of a minor or lunatic)? Are art exhibitions “spiritual undertakings with the power to conjure alternative ways of organizing society,” or vehicles for cultural tourism and nationalistic propaganda?

These splits, which reflect larger tears in the social fabric, certainly in the United States, complicate the changing role of curators of contemporary art, because curators mediate between art and its publics and are often forced to take “a curving and indirect course” between them. Teaching for the past five years at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, I observed young curators confronting the practical demands and limitations of their profession armed with a vision of possibility and an image of the curator as a free agent, capable of almost anything. Where did this image come from?

When Harald Szeemann and Walter Hopps died in February and March 2005, at age 72 and 71, respectively, it was impossible not to see this as the end of an era. They were two of the principal architects of the present approach to curating contemporary art, working over 50 years to transform the practice. When young curators imagine what’s possible, they are imagining (whether they know it or not) some version of Szeemann and Hopps. The trouble with taking these two as models of curatorial possibility is that both of them were sui generis: renegades who managed, through sheer force of will, extraordinary ability, brilliance, luck, and hard work, to make themselves indispensable, and thereby intermittently palatable, to the conservative institutions of the art world.

Each came to these institutions early. When Szeemann was named head of the Kunsthalle Bern in 1961, at age 28, he was the youngest ever to have been appointed to such a position in Europe, and when Hopps was made director of the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum) in 1964, at age 31, he was then the youngest art museum director in the United States. By that time, Hopps (who never earned a college degree) had already mounted a show of paintings by Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, Jay DeFeo, and many others on a merry-go-round in an amusement park on the Santa Monica Pier (with his first wife, Shirley Hopps, when he was 22); started and run two galleries (Syndell Studios and the seminal Ferus Gallery, with Ed Kienholz); and curated the first museum shows of Frank Stella’s paintings and Joseph Cornell’s boxes, the first U.S.retrospective of Kurt Schwitters, the first museum exhibition of Pop Art, and the first solo museum exhibition of Marcel Duchamp, in Pasadena in 1963. And that was just the beginning. Near the end of his life, Hopps estimated that he’d organized 250 exhibitions in his 50-year career.

Szeemann’s early curatorial activities were no less prodigious. He made his first exhibition, Painters Poets/ Poets Painters, a tribute to Hugo Ball, in 1957, at age 24. When he became the director of the Kunsthalle in Bern four years later, he completely transformed that institution, mounting nearly 12 exhibitions a year, culminating in the landmark show Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, in 1969, exhibiting works by 70 artists, including Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Eva Hesse, Lawrence Weiner, Richard Long, and Bruce Nauman, among many others.

While producing critically acclaimed and historically important exhibitions, both Hopps and Szeemann quickly came into conflict with their respective institutions. After four years at the Pasadena Art Museum, Hopps was asked to resign. He was named director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1970, then fired two years later. For his part, stunned by the negative reaction to When Attitudes Become Form from the Kunsthalle Bern, Harald Szeemann quit his job, becoming the first “independent curator.” He set up the Agency for Spiritual Guestwork and co-founded the International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art (IKT) in 1969, curated Happenings & Fluxus at the Kunstverein in Cologne in 1970, and became the first artistic director of Documenta in 1972, reconceiving it as a 100-day event. Szeemann and Hopps hadn’t yet turned 40, and their best shows were all ahead of them. For Szeemann, these included Junggesellenmaschinen—Les Machines célibataires (“Bachelor Machines”) in 1975-77, Monte Veritá (1978, 1983, 1987), the first Aperto at the Venice Biennale (with Achille Bonito Oliva, 1980), Der Hang Zum Gesamtkunstwerk, Europaïsche Utopien seit 1800 (“The Quest for the Total Work of Art”) in 1983-84, Visionary Switzerland in 1991, the Joseph Beuys retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 1993, Austria in a Lacework of Roses in 1996, and the Venice Biennale in 1999 and 2001. For Hopps, yet to come were exhibitions of Diane Arbus in the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1972, the Robert Rauschenberg mid-career survey in 1976, retrospectives at the Menil Collection of Yves Klein, John Chamberlain, Andy Warhol, and Max Ernst, and exhibitions of Jay DeFeo (1990), Ed Kienholz (1996 at the Whitney), Rauschenberg again (1998), and James Rosenquist (2003 at the Guggenheim). Both Szeemann and Hopps had exhibitions open when they died—Szeemann’s Visionary Belgium, for the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, and Hopps’s George Herms retrospective at the Santa Monica Museum—and both had plans for many more exhibitions in the future.

What Do Curators Do?

Szeemann and Hopps were the Cosmas and Damian (or the Beuys and Duchamp) of contemporary curatorial practice. Rather than accepting things as they found them, they changed the way things were done. But finally, they will be remembered for only one thing: the quality of the exhibitions they made; for that is what curators do, after all. Szeemann often said he preferred the simple title of Ausstellungsmacher (exhibition-maker), but he acknowledged at the same time how many different functions this one job comprised: “administrator, amateur, author of introductions, librarian, manager and accountant, animator, conservator, financier, and diplomat.” I have heard curators characterized at different times as:

Administrators Advocates

Auteurs

Bricoleurs (Hopps’ last show, the Herms retrospective, was titled “The Bricoleur of Broken Dreams. . . One More Once”)

Brokers

Bureaucrats

Cartographers (Ivo Mesquita)

Catalysts (Hans Ulrich Obrist)

Collaborators

Cultural impresarios

Cultural nomads

Diplomats (When Bill Lieberman, who held top curatorial posts at both the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, died in May 2005, Artnews described him as “the consummate art diplomat”)

And that’s just the beginning of the alphabet. When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked Walter Hopps to name important predecessors, the first one he came up with was Willem Mengelberg, the conductor of the New York Philharmonic, “for his unrelenting rigor.” He continued, “Fine curating of an artist’s work—that is, presenting it in an exhibition—requires as broad and sensitive an understanding of an artist’s work that a curator can possibly muster. This knowledge needs to go well beyond what is actually put in the exhibition. . . . To me, a body of work by a given artist has an inherent kind of score that you try to relate to or understand. It puts you in a certain psychological state. I always tried to get as peaceful and calm as possible.”3

But around this calm and peaceful center raged the “controlled chaos” of exhibition making. Hopps’ real skills included an encyclopedic visual memory, the ability to place artworks on the wall and in a room in a way that made them sing,4 the personal charm to get people to do things for him, and an extraordinary ability to look at a work of art and then account for his experience of it, and articulate this account to others in a compelling and convincing way.

It is significant, I think, that neither Szeemann nor Hopps considered himself a writer, but both recognized and valued good writing, and solicited and “curated” writers and critics as well as artists into their exhibitions and publications. Even so, many have observed that the rise of the independent curator has occurred at the expense of the independent critic. In a recent article titled “Do Art Critics Still Matter?” Mark Spiegler opined that “on the day in 1969 when Harald Szeemann went freelance by leaving the Kunsthalle Bern, the wind turned against criticism.”5 There are curators who can also write criticism, but these precious few are exceptions that prove the rule. Curators are not specialists, but for some reason they feel the need to use a specialized language, appropriated from philosophy or psychoanalysis, which too often obscures rather than reveals their sources and ideas. The result is not criticism, but curatorial rhetoric. Criticism involves making finer and finer distinctions among like things, while the inflationary writing of curatorial rhetoric is used to obscure fine distinctions with vague generalities. The latter’s displacement of the former has a political dimension as we move into an increasingly managed, post-critical environment.

Although Szeemann and Hopps were very different in many ways, they shared certain fundamental values: an understanding of the importance of remaining independent of institutional prejudices and arbitrary power arrangements; a keen sense of history; the willingness to continually take risks intellectually, aesthetically, and conceptually; and an inexhaustible curiosity about and respect for the way artists work.

![]() Portrait of Walter Hopps. Pencil and Paper by Phong Bui.

Portrait of Walter Hopps. Pencil and Paper by Phong Bui.Szeemann’s break away from the institution of the Kunsthalle was, simply put, “a rebellion aimed at having more freedom.”6 This rebellious act put him closer to the ethos of artists and writers, where authority cannot be bestowed or taken, but must be earned through the quality of one’s work. In his collaborations with artists, power relations were negotiated in practice rather than asserted as fiat. Every mature artist I know has a favorite horror story about a young, inexperienced curator trying to claim an authority they haven’t earned by manipulating a seasoned artist’s work or by designing exhibitions in which individual artists’ works are seen as secondary and subservient to the curator’s grand plan or theme. The cure for this kind of insecure hubris is experience, but also the recognition of the ultimate contingency of the curatorial process. As Dave Hickey said of both critics and curators, “Somebody has to do something before we can do anything.”7 In June of 2000, after being at the pinnacle of curatorial power repeatedly for over 40 years, Harald Szeemann said, “Frankly, if you insist on power, then you keep going on in this way. But you must throw the power away after each experience, otherwise it’s not renewing. I’ve done a lot of shows, but if the next one is not an adventure, it’s not important for me and I refuse to do it.”8

When contemporary curators, following in the steps of Szeemann, break free from institutions, they sometimes lose their sense of history in the process. Whatever their shortcomings, institutions do have a sense (sometimes a surfeit) of history. And without history, “the new” becomes a trap, a sequential recapitulation of past approaches with no forward movement. It is a terrible thing to be perpetually stuck in the present, and this is a major occupational hazard for curators.

Speaking about his curating of the Seville Biennale in 2004, Szeemann said, “It’s not about presenting the best there is, but about discovering where the unpredictable path of art will go in the immanent future.” But moving the ball up the field requires a tremendous amount of legwork. “The unpredictable path of art” becomes much less so when curators rely on the Claude Rains method, rounding up the usual suspects from the same well-worn list of artists that everyone else in the world is using.

It is difficult, in retrospect, to fully appreciate the risks that both Szeemann and Hopps took to change the way curators worked. One should never underestimate the value of a monthly paycheck. By giving up a secure position as director of a stable art institution and striking out on his own as an “independent curator,” Szeemann was assuring himself years of penury. There was certainly no assurance that anyone would hire him as a freelance. Anyone who’s chosen this path knows that freelance means never having to say you’re solvent. Being freelance as a writer and critic is one thing: The tools of the trade are relatively inexpensive, and one need only make a living. But making exhibitions is costly and finding “independent” money, money without onerous strings attached to it, is especially difficult when one cannot, in good conscience, present it as an “investment opportunity.” Daniel Birnbaum points out that “all the dilemmas of corporate sponsorship and branding in contemporary art today are fully articulated in [‘When Attitudes Become Form’]. Remarkably, according to Szeemann, the exhibition came about only because ‘people from Philip Morris and the PR firm Ruder Finn came to Bern and asked me if I would do a show of my own. They offered me money and total freedom.’ Indeed, the exhibition’s catalogue seems uncanny in its prescience: ‘As businessmen in tune with our times, we at Philip Morris are committed to support the experimental,’ writes John A. Murphy, the company’s European president, asserting that his company experimented with ‘new methods and materials’ in a way fully comparable to the Conceptual artists in the exhibition. (And yet, showing the other side of this corporate-funding equation, it was a while before the company supported the arts in Europe again, perhaps needing time to recover from all the negative press surrounding the event.)”9 So the founding act of “independent curating” was brought to you by . . . Philip Morris! 33 years later, for the Swiss national exhibition Expo.02, Szeemann designed a pavilion covered with sheets of gold, containing a system of pneumatic tubes and a machine that destroyed money—two 100 franc notes every minute during the 159 days of the exhibition. The sponsor? The Swiss National Bank, of course.

When Walter Hopps brought the avant-garde to Southern California, he didn’t have to compete with others to secure the works of Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, or Jay DeFeo (for the merry-go-round show in 1953), because no one else wanted them. In his Hopps obituary, Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight pointed out that “just a few years after Hopps’s first visit to the [Arensbergs’] collection, the [Los Angeles] City Council decreed that Modern art was Communist propaganda and banned its public display.”10 In 50 years, we’ve progressed from banning art as Communist propaganda to prosecuting artists as terrorists.11

The Few and Far Between

It’s not that fast horses are rare, but men who know enough to spot them

are few and far between.

—Han Yü12

The trait that Szeemann and Hopps had most in common was their respect for and understanding of artists. They never lost sight of the fact that their principal job was to take what they found in artists’ works and do whatever it took to present it in the strongest possible way to an interested public. Sometimes this meant combining it with other work that enhanced or extended it. This was done not to show the artists anything they didn’t already know, but to show the public. As Lawrence Weiner pointed out in an interview in 1994, “Everybody that was in the Attitudes show knew all about the work of everybody else in the Attitudes show. They wouldn’t have known them personally, but they knew all the work. . . . Most artists on both sides of the Atlantic knew what was being done. European artists had been coming to New York and U.S. artists went over there.”13 But Attitudes brought it all together in a way that made a difference.

Both Szeemann and Hopps felt most at home with artists, sometimes literally. Carolee Schneemann recently described for me the scene in the Kunstverein in Cologne in 1970, when she and her collaborator in “Happenings and Fluxus” (having arrived and discovered there was no money for lodging) moved into their installations, and Szeemann thought it such a good idea to sleep on site that he brought in a cot and slept in the museum himself, to the outrage of the guards and staff. Both Szeemann and Hopps reserved their harshest criticism for the various bureaucracies that got between them and the artists. Hopps once described working for bureaucrats when he was a senior curator at the National Collection of Fine Arts as “like moving through an atmosphere of Seconal.”14 And Szeemann said in 2001 that “the annoying thing about such bureaucratic organizations as the [Venice] Biennale is that there are a lot of people running around who hate artists because they keep running around wanting to change everything.”15 Changing everything, for Szeemann, was just the point. “Artists, like curators, work on their own,” he said in 2000, “grappling with their attempt to make a world in which to survive. . . . We are lonely people, faced with superficial politicians, with donors, sponsors, and one must deal with all of this. I think it is here where the artist finds a way to form his own world and live his obsessions. For me, this is the real society.”16 The society of the obsessed.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Although Walter Hopps was an early commissioner for the São Paolo Biennal (1965: Barnett Newman, Frank Stella, Richard Irwin and Larry Poons) and of the Venice Biennale (1972: Diane Arbus), Harald Szeemann practically invented the role of nomadic independent curator of huge international shows, putting his indelible stamp on Documenta and Venice and organizing the Lyon Biennale and the Kwangju Biennial in Korea in 1997, and the first Seville Biennale in 2004, as well as numerous other international surveys around the world.

So what Szeemann said about globalization and art should perhaps be taken seriously. He saw globalization as a euphemism for imperialism, and proclaimed that “globalization is the great enemy of art.” And in the Carolee Thea interview in 2000, he said, “Globalization is perfect if it brings more justice and equality to the world . . . but it doesn’t. Artists dream of using computers or digital means to have contact and to bring continents closer. But once you have the information, it’s up to you what to do with it. Globalization without roots is meaningless in art.”17 And globalization of the curatorial class can be a way to avoid or “transcend” the political.

Rene Dubos’s old directive to “think globally, but act locally” (first given at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972) has been upended in some recent international shows (like the 14th Sydney Biennale in 2004, and the 1st Moscow Biennial in 2005). When one thinks locally (within a primarily Euro-American cultural framework, or within a New York-London-Kassel-Venice-Basel-Los Angeles-Miami framework) but acts globally, the results are bound to be problematic, and can be disastrous. In 1979, Dubos argued for an ecologically sustainable world in which “natural and social units maintain or recapture their identity, yet interplay with each other through a rich system of communications.” At their best, the big international exhibitions do contribute to this. Okwui Enwezor’s18 Documenta XI certainly did, and Szeemann knew it. At their worst, they perpetuate the center-to-periphery hegemony and preclude real cross-cultural communication and change. Although having artists and writers move around in the world is an obvious good, real cultural exchange is something that must be nurtured. Walter Hopps said in 1996: “I really believe in—and, obviously, hope for—radical, or arbitrary, presentations, where cross-cultural and cross-temporal considerations are extreme, out of all the artifacts we have. . . . So just in terms of people’s priorities, conventional hierarchies begin to shift some.”19

The Silence of Szeemann & Hopps Is Overrated

‘Art’ is any human activity that aims at producing improbable situations, and it is the more artful (artistic) the less probable the situation that it produces. —Vilém Flusser20

Harald Szeemann recognized early and long appreciated the utopian aspects of art. “The often-evoked ‘autonomy’ is just as much a fruit of subjective evaluation as the ideal society: it remains a utopia while it informs the desire to experientially visualize the unio mystica of opposites in space. Which is to say that without seeing, there is nothing visionary, but that the visionary should always determine the seeing.” And he recognized that the bureaucrat could overtake the curer of souls at any point. “Otherwise, we might just as well return to ‘hanging and placing,’ and divide the entire process ‘from the vision to the nail’ into detailed little tasks again.”21 He organized exhibitions in which the improbable could occur, and was willing to risk the impossible. In reply to a charge that the social utopianism of Joseph Beuys was never realized, Szeemann said, “The nice thing about utopias is precisely that they fail. For me, failure is a poetic dimension of art.”22 Curating a show in which nothing could fail was, to Szeemann, a waste of time.

If he and Hopps could still encourage young curators in anything, I suspect it would be to take greater risks in their work. At a time when all parts of the social and political spheres (including art institutions) are increasingly managed, breaking out of this frame, asking significant questions, and setting the terms of resistance is more and more vitally important. It is important to work against the bias of the world (commodity, political expediency). For curators of contemporary art, that means finding and supporting those artists who, as Flusser writes, “have attempted, at the risk of their lives, to utter that which is unutterable, to render audible that which is ineffable, to render visible that which is hidden.”23

This essay will be included in the forthcoming Cautionary Tales: Critical Curating

Edited by Steven Rand and Heather Kouris, published by Apex Art. It will be available by January 2007.

Endnotes

1 Shakespeare, The Life and Death of King John, Act II, Scene 1, 573-74. Cowper: “What Shakespeare calls commodity, and we call political expediency.” Appendix 13 of my old edition of Shakespeare’s Complete Works, edited by G. B. Harrison (NY: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968), pp. 1639-40, reads: “Shakespeare frequently used poetic imagery taken from the game of bowls [bowling]. . . . The bowl [bowling ball] was not a perfect sphere, but so made that one side somewhat protruded. This protrusion was called the bias; it caused the bowl to take a curving and indirect course.”

2 “When Attitude Becomes Form: Daniel Birnbaum on Harald Szeemann,” Artforum, Summer 2005, p. 55.

3 Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews, Volume I, edited by Thomas Boutoux (Milan: Edizioni Charta, 2003), pp. 416-17. Hopps also named as predecessors exhibition-makers Katherine Dreier, Alfred Barr, James Johnson Sweeney, René d’Harnoncourt, and Jermayne MacAgy.

4 In 1976, at the Museum of Temporary Art in Washington, D.C., Hopps announced that, for thirty-six hours, he would hang anything anyone brought in, as long as it would fit through the door. Later, he proposed to put 100,000 images up on the walls of P.S. 1 in New York, but that project was, sadly, never realized.

5 Mark Spiegler, “Do Art Critics Still Matter?” The Art Newspaper, no. 157, April 2005, p. 32.

6 Carolee Thea, Foci: Interviews with Ten International Curators (New York: Apex Art Curatorial Program, 2001), p. 19.

7 Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility: Proceedings from a symposium addressing the state of current curatorial practice organized by the Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative, October 14-15, 2000, edited by Paula Marincola (Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative, 2001), p. 128. Both Szeemann and Hopps passed Hickey’s test: “The curator’s job, in my view,” he said, “is to tell the truth, to show her or his hand, and get out of the way” (p. 126).

8 Carolee Thea, p. 19 (emphasis added).

9 Daniel Birnbaum, p. 58.

10 Christopher Knight, “Walter Hopps, 1932-2005. Curator Brought Fame to Postwar L.A. Artists,” Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2005.

11At this writing, the U.S. government continues in its effort to prosecute artist Steven Kurtz for obtaining bacterial agents through the mail, even though the agents were harmless and intended for use in art pieces by the collaborative Critical Art Ensemble. Kurtz has said he believes the charges filed against him in 2004 (after agents from the FBI, the Joint Terrorism Task Force, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Depeartment of Defence swarmed over his house) are part of a Bush administration campaign to prevent artists from protesting government policies. “I think we’re in a very unfortunate moment now in U.S. history,” Kurtz has said. “A form of neo-McCarthyism has made a comeback. . . . We’re going to see a whole host of politically motivated trials which have nothing to do with crime but everything to do with artistic expression.” For the latest developments in the case, go to caedefensefund.org.

12 Epigraph to Nathan Sivin’s Chinese Alchemy: Preliminary Studies(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968).

13 Having Been Said: Writings & Interviews of Lawrence Weiner 1968-2003, edited by Gerti Fietzek and Gregor Stemmrich (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2004), p. 315.

14 Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Walter Hopps Hopps Hopps—Art Curator,” Artforum, February 1996.

15 Jan Winkelman, “Failure as a Poetic Dimension: A Conversation with Harald Szeemann,” Metropolis M. Tijdschrift over Hedendaagse Kunst, No. 3, June 2001.

16 Carolee Thea, p. 17 (emphasis added).

17 Carolee Thea, p. 18.

18 With his co-curators Carlos Basualdo, Uta Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj, Mark Nash, and Octavio Zaya.

19 Hans Ulrich Obrist, p. 430.

20 Vilém Flusser, “Habit: The True Aesthetic Criterion,” in Writings, edited by Andreas Ströhl, translated by Erik Eisel (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), p. 52.

21 Harald Szeemann, “Does Art Need Directors?” in Words of Wisdom: A Curator’s Vade Mecum on Contemporary Art, edited by Carin Kuoni (New York: Independent Curators International, 2001), p. 169.

22 Jan Winkelman.

23 Flusser, p. 54.

Copyright

=========

WHEN ATTITUDES BECOME FORM

Barry Barker |

| Flash Art n. 275 – November – December 2010

AMARCORD

LIVE IN YOUR HEAD

TO REFLECT UPON an exhibition that took place over 40 years ago is a strange and salutary experience, and I am grateful that I still have the faculties to recall “Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form,” the exhibition I visited at the Institute ofContemporary Arts in London in September 1969. During the late ’60s through the mid-’70s, it was often considered inappropriate or irrelevant to critically refer to an artwork’s context or its authorship. It was the time of the “death of the author,” when any understanding of the work of art was to come solely from its own presence, withoutreference to metaphor, biography or any other outside circumstances. It now seems commonplace to consider the context of a work of art, which could be said to carry at least fifty percent of its meaning, whether it is relating to its materiality, physicality in terms of place, or social and cultural position. Looking back on this exhibition, context seems especially relevant. |

|

| From top left: (1, 7, 8, 9, 11) Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. Installation views during the opening event at Kunsthalle Bern, 1969. © Kunsthalle Bern,Bern. (2, 3, 4, 5, 10) Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. Installation views of the exhibition during the opening event at Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, 1969. (6) Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. Harald Szeemann during the opening event at Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, 1969; sitting in the audience: Paul Wember, Director of Kunstmuseen Krefeld in 1969. (12) Live in your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. Paul Wember and artist Sarkis with two of the artist’s works during the opening event at Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, 1969; on the wall,Robert Morris, Batteries with Ripples, 1964; Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, 1969. |

|

|

| In 1968, the I.C.A. had moved from a small space in Dover Street to larger premises in the Carlton House Terrace, which backed on to the Mall, the road that leads to Buckingham Palace. This juxtaposition — the home of the British monarch close by what was meant to house the UK’s cultural avant-garde — was itself a paradox. This was the first time I’d visited this new I.C.A., but I had read and to some extent seen much of the work in “Attitudes” while traveling, and therefore was familiar with many of the artists in the exhibition. I walked down a few steps into an open, modestly largespace; it was obviously not an industrial space and bore the signs of being the ex-stables and coach house for the above apartments’ grand occupants of 18th-century aristocracy. The exhibition was curated and selected by the late Harald Szeemann, at the time director of Kunsthalle Bern, where the exhibition was first shown. The title was interesting in itself, as it implied the bringing together of ideas and thoughts, and their ability to inspire the formation of a material presence. Though in some instances they did the opposite, staying in the realms of language, or existing as works that — to quote the front of the catalogue — “live in your head,” which was the original title of ArthurMiller’s play Death of a Salesman (1949). The exhibition was conceived and curated notas a means of defining or fixing the art of its time, but the absolute opposite: to open up the concept of art and to change human perception of contemporary art as it was then understood. To quote Szeemann in his introductionto the catalogue, “In order to entertain certain ideas we may be obliged to abandon others upon which we have come to depend.” This exhibition was and still is a prime example of a curator responding to the work of contemporary artists, letting the artists provide the initiative rather than the curator imposing their personal theories or worldview, as often happens today. The subtitle to the exhibition, “Works-Concepts-Processes-Situations-Information,” in many ways describes its contents. These works asked spectators to join the artist in stepping outside their comfort zone — to allow

their consciousness to be realigned with a new order of things.

This was a time when many artists, writers and gallery directors, whether working withinan institutional or private context, found themselves in a world in which their vocation and even their aspirations no longer fit happily within a traditional definition of art or culture. There appeared to be a chasm between language, ideas and the world. Protests against the Vietnam War were at their height both in America and Europe. Lacking a fixed cultural order in equilibrium with the past, artists found themselves in a place of disenchantment. In a positive sense, however, it was also a time of discussion, idea exchange and information. The world was becoming a smaller place; every artist and thinker felt that there were many ideas and places to explore, yet they in turn had something to contribute to the cultural life of a global environment. It was in this spiritthat Szeemann researched and brought to light artistic developments of a younger generation. “When Attitudes Become Form” traveled from Kunsthalle Bern to the Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld (Germany) to the I.C.A. London like a caravan traveling through a cultural desert from one oasis to another, picking up more local goods as it went along. It was brought to London on the initiative of the late Charles Harrison, who was a writer, freelance curator and assistant editor of the magazine Studio International.Harrison was approached by the sponsor of the exhibition, cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris, who offered to finance this ‘caravan.’ At the time, Harrison was planning an exhibition of his own, but he lacked funding. So instead he agreed to bring “Attitudes” to the I.C.A. if he could add his own selection of British artists, such as Victor Burgin (though he did not include the Art & Language group, which he was associated with). At that time, the I.C.A.’s director had little experience with visual art, let alone contemporary visual art (his discipline was in the theater), and so the institution accepted the show mainly for financial reasons — in other words because it was more-or-less free. Still, Harrison resented not being able to curate his own show, so much sothat when Harald Szeemann came to London for the opening, Harrison is quoted as saying that he “hardly talked to him.” |

|

| From top left clockwise: JOSEPH BEUYS, Jason, 1961. Live in your Head: When Attitudes become Form. installation view at Haus Lange Krefeld, 1969. ROBERT MORRIS, Felt Piece no. 4, 1968. GILBERTO ZORIO, Untitled (Torcia), 1969. JANNIS KOUNELLIS, Senza Titolo, 1969. All courtesy Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Germany.Photos: Archive Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Germany. |

|

|

| As soon as I saw the exhibition laid out before me I felt the mixed emotions of beingcaptivated and disappointed at the same time. As I came down the steps, on my left was a series of sacks that contained different kinds of grains [Jannis Kounellis, untitled, 1969]. Some visitors took handfuls and chewed them while viewing the exhibition and others threw them on the gallery floor. Some artists were invited by the sponsor to come to London and install their work; one of them was Reiner Ruthenbeck, from Germany, and it was his piece that drew my attention next, which consisted of tangled wire amid a pile of ashes [Aschenhaufen III, 1968] and was said to be about German war guilt. Ger Van Elk was invited to London to shave a cactus, which was filmed and then placed forlornly on a low brick wall in the gal lery [The Well Shaven Cactus, 1969]. JosephKosuth put statements in several of London’s local newspapers.

As for the disappointments, there were many. The installation of Eva Hesse’s works

somehow did not look convincing; it was some years later that Harrison admitted he

hadn’t installed them correctly through lack of instructions. Another disappointment wasthat Lawrence Weiner’s ‘wall removal’ [A 36 x 36 Removal to the Lathing or Support Wallof Plaster, 1968] was not ‘installed.’ However, the one major omission was of a work by an artist who we all wished to know more about at the time: Joseph Beuys. Beuys had been invited to the exhibition, and he offered a new work comprised of a Volkswagen Microbus and twenty-two sleds with fat and felt [Das Rudel (The Pack), 1969]. The I.C.A. could not afford the transport cost, so the British Public lost out on seeing this major 20th-century work for the first time. In his introduction to the exhibition, Szeemannstated: “The exhibition appears to lack unity.” “[It]…gathers a number of artists whose work has very little in common yet also a great deal in common.” In hindsight, his remarks are understandable because the exhibition reflected so many different directions that were subsequently categorized as conceptual art, minimal art, arte povera, land art and installation art. One unifying aspect was the radical economy and simplicity of the artworks’ means and materials. Artists used common materials such as rope, wood, canvas, photocopy and language, often to greater effect than today’s artists who spend huge sums of money on fabrication.

In Bern, the exhibition so outraged the Swiss public that a few days after the opening

protesters placed a pile of dung in front of the Kunsthalle’s entrance. Yet in London

the attitude to the show was one of indifference; as long as there was no public fundingit could be happily ignored. I have come to believe that the Swiss public resented thefact that the exhibition had an English title together with the fact that it was sponsoredby an American company (Szeemann had already been accused by the Kunsthalle’s board of trustees of not showing enough Swiss artists). A month after the closing of the exhibition, Harald Szeemann resigned, going on to develop a more nomadic mode of working that has come to define much of today’s curatorial practice.

Barry Barker is a curator and writer based in London. He is Fellow of the University ofBrighton, UK. “Amarcord” is a new series of feature articles where Flash Art Internationalinvites writers and curators to discuss landmark exhibitions from the past.

Special thanks to Karin Minger of Kunsthalle Bern, and to Dr. Sabine Röder and Volker Döhne, respectively Curator and Photographer, of Kunstmuseen Krefeld, Germany. |

|

|

======

The man who turned everything into art

Did Harald Szeemann single-handedly invent the idea of the contemporary curator? Three new books make the case

By The Art Newspaper. Books, Issue 191, May 2008

Published online: 01 May 2008

It is now widely accepted that the art history of the second half of the 20th century is no longer a history of artworks, but a history of exhibitions,” states—rather provocatively—the introduction to Harald Szeemann: Individual Methodology. A concomitant phenomenon is the emergence of a new profession, namely that of the curator, and Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) is often credited with inventing the job.

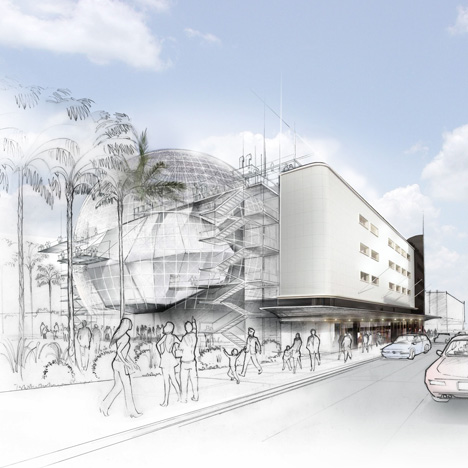

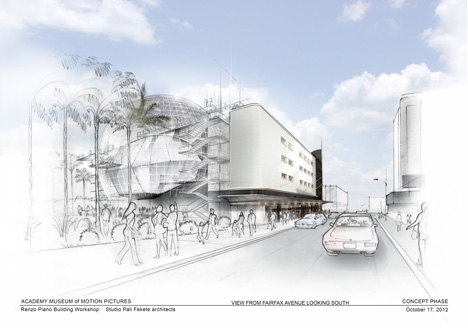

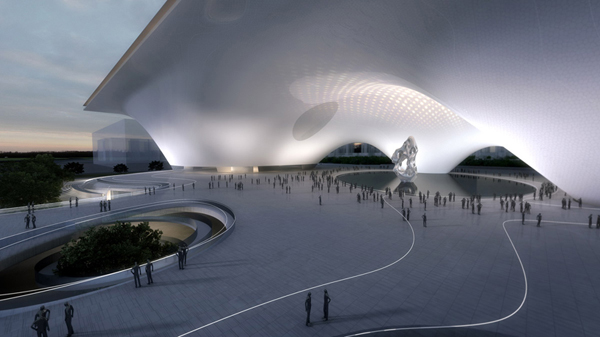

Between 1957 and 2005, the Bern-born Szeemann organised a staggering number and variety of exhibitions, working in close collaboration with artists, exploring new forms of displaying art, redefining the role of the museum and ultimately expanding the notion of art. In 1961, he was appointed director of the Kunsthalle, Bern, where he staged monographic and thematic shows of contemporaries as well as displaying the art of the mentally ill and science fiction paraphernalia. His activity there culminated with the groundbreaking and controversial “When Attitudes Become Form” (1969), which saw Michael Heizer smash up the pavement outside the museum, while inside Richard Serra flung hot lead against the wall. The show eventually triggered Szeemann’s resignation. He went freelance, founding the deliciously named one-man band Agency for Intellectual Guest Labour, which applied to the museum the system of guest performances familiar to him from an early spell as a one-man theatre. He was appointed general secretary of Documenta 5 (1972), displayed his hairdresser grandfather’s belongings in his own flat (1974) and embarked on a series of highly original and ambitious thematic shows including “The Bachelor Machines” (1975), “Monte Verità” (1978) and “The Penchant for the Gesamtkunstwerk” (1983). From 1981 until 2000, he also held the position of permanent independent collaborator at the Kunsthaus, Zurich. In the 1980s, he staged a series of “auratic” sculpture exhibitions as “poems in space”. The 1990s saw him in great demand as an organiser of large-scale international surveys (including the 1999 and 2001 Venice Biennials) and striking out further afield, for example to Eastern Europe’s emerging contemporary art scenes. His last exhibition, “Visionary Belgium” (2005), was the

third in a trilogy of “mental-spiritual” country portraits

after “Visionary Switzerland” (1991) and “Austria in a Net

of Roses” (1996).

Next to works of art, object categories that found their way into Szeemann’s thematic shows included puppets, robots, machines, magazine covers, banknotes, propaganda, advertising, comics, personal memorabilia, utopian project documentation and architectural models—a real “Wunderkammer” which triggered free association and flash-like insights, making his exhibitions journeys through one’s own head as much as physical walks through space.

Despite this approach—more reminiscent of cultural anthropology than art history—Szeemann always held on to art’s position as an irreducible other, something different and apart. Not for him the equation of art and life or art’s immediate social and collective relevance, sought for and conjured by so many of his contemporaries. Accused by some of reverting to “art for art’s sake”, he countered with the primacy of the non-collective utopias he termed individual mythologies and his view of art as “a sum of narrations in the first person singular”: a reflection of his fascination both with those at the margins and resisting socialisation (outsiders, freaks and monomaniacs as much as artists) and with the notion of intensity, which served as the main criterion of his “tirelessly working art metabolism” (to

a traditional art history of

great masterpieces, he thus preferred an “art history of intensive intentions”).

Beginning in 1973, he put his Agency at the service of a Museum of Obsessions—his own as much as those of artists and creators. Indeed, so strongly did he extol the exhibition as a medium of expression rather than a merely mediatory activity that some accused him of turning it into a work of art, using the individual works on display as so many “touches of colour”. While Szeemann refuted this status as an artist, he did claim that of an author, staging deeply subjective shows.

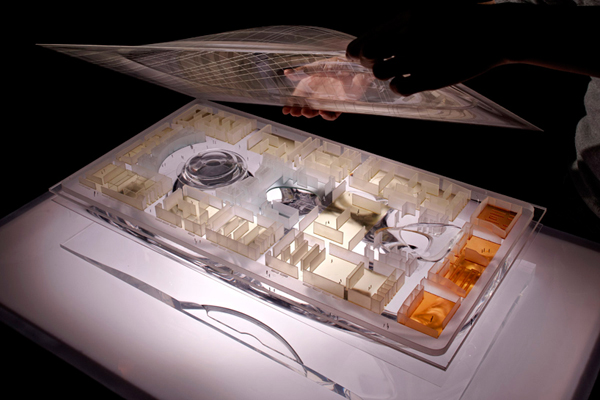

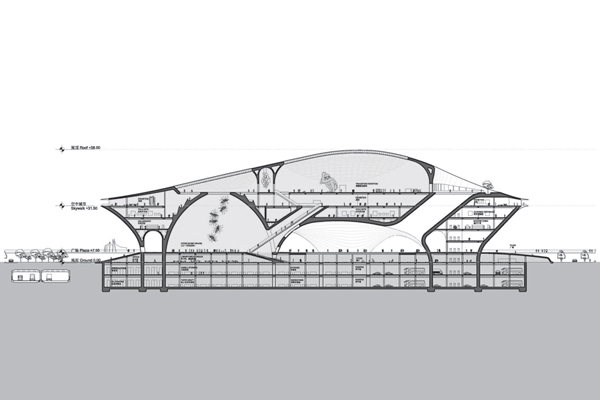

Indeed, with its subtitle Catalogue of all Exhibitions 1957-2005, Harald Szeemann – with by through because towards despite flirts with the format of the catalogue raisonné, with over 150 entries which list information about catalogues, admission figures, tour venues and related events as well as reproducing selected press articles and exhibition reviews, interviews, exhibition floor plans, installation views, catalogue covers and exhibition posters, catalogue texts, Szeemann’s correspondence (including an irate letter from feminist art critic and curator Lucy Lippard), photographs with family and friends, and Szeemann’s own contemporary and retrospective notes and commentaries (the publication was originally conceived and produced in cooperation with Szeemann, and in view of his annotations’ lively, insightful and richly anecdotal character, one wishes they were even more numerous). An extensive bibliography completes the volume. Maybe the most telling document is Szeemann’s original address-list of artists in preparation for “When Attitudes Become Form” which, coupled with his travel diary, brings to life his frantic pace of studio and gallery visits. Editors

Tobia Bezzola and Roman Kurzmeyer, who both knew and collaborated with him on numerous projects, have compiled a dazzling panorama

of planet Szeemann.

While the Catalogue relies mainly on primary source material, Harald Szeemann: Exhibition Maker provides a more interpretive and discursive account of the curator’s career, organised along a general chronology but zooming in on major exhibitions, elegantly leaping from milestone to milestone and laying bare with fascinating clarity the internal logic driving the progression of Szeemann’s body of exhibitions. Art critic Hans-Joachim Müller also knew and worked with Szeemann, and this is a tender and incisive portrait by someone who candidly admits falling under the spell of “the maelstrom of Szeemann’s exhibitions, the fatal attraction of his fantasies, discoveries, assertions, these panoramas that he unfolded like paper scenes”. Interwoven with well-chosen photographs, this is a dense, beautifully composed text, which makes it the more

a pity that the English translation should be so strangely inconsistent, at times elegant, at others all but incomprehensible.

Finally, Harald Szeemann: Individual Methodology, the result of a research project of the International Curatorial Training Programme of Le Magasin, Grenoble, is the first in a series of curatorial notebooks developed jointly with the Department of Curating Contemporary Art at London’s Royal College of Art and was conceived as a companion to the Catalogue. The programme’s eight participants were granted access to Szeemann’s archive, located since 1986 at the Fabbrica Rosa near Locarno in Switzerland, which also functioned as the Agency for Intellectual Guest Labour’s headquarters: 300 sq. metres of structured chaos consisting of books, press clippings, correspondence, project documentation and objects assembled relentlessly since the early 1960s and kept in part

in empty wine cases of Szeemann’s favourite Merlot. Based on partly unpublished documents and interviews with close collaborators, the publication analyses the archive and the Agency as twin tools of Szeemann’s curatorial practice and examines in detail two of his projects, Documenta 5 (1972) and the Lyon Biennial (1997). The photographs of the archive are particularly engrossing.

Together and on their own, these three felicitously complementary publications function as fascinating insights into the universe of a man for whom each exhibition was an opportunity to create a temporary world and who still towers over the profession he pioneered.

Maud Capelle

![]()

June 2001 – Vol.20 No.5

|

Here Time Becomes Space:

A Conversation with Harald Szeemann

by Carol Thea

|

Harald Szeemann is a standard-bearer of change within the European curatorial tradition. He holds degrees in art history, archaeology, and journalism. Between 1961 and 1969 he served as director of the Kunsthalle Bern. Since he declared his independence by resigning his directorship in 1969, he has become one of the most important and active international independent curators, organizing such major exhibitions as “When Attitudes Become Form” (1969), “Happening and Fluxus” (1970), Documenta 5 (1972), “Bachelor Machines” (1975), “Monte Verità: Mountain of Truth” (1978), “Charles Baudelaire” (1987), and “Austria in a Lacework of Roses” (1996). He co-organized the Venice Biennale of 1980, where he created the Aperto, an exhibition for younger and emerging artists. Since 1981 he has been an independent curator affiliated with the Kunsthaus Zurich. He was the director of the 1997 Lyon Biennale, a commissioner of the 1997 Kwangju Biennial, and has been director of the Venice Biennale in 1999 and 2001. His exhibition in the Italian Pavilion of the Biennale, “The Plateau of Mankind,” officially opens June 9th and closes November 4th.

![]()

Collaborative work by Barry McGee, Stephen Powers, and James Todd. Artists chosen by Harald Szeemann for the 2001 Venice Biennale exhibition, “The Plateau of Mankind.” |

Carolee Thea: The artist’s work is a seismograph of change in a society. When contemplating an exhibition, the curator must have a finger on this pulse, on the collective concerns of the moment, as well as on the more individual ones that inform an artist’s narrative.

Harald Szeemann: Yes, I also think that the curator has his own evolution. When you’ve been doing exhibitions for 43 years, you come to a certain point: the facteur Cheval said that with 43 years a human being reaches the equinox of life and can start to build his castle in the air, his “Palais idéal.” From this moment on, even if you do a show with contemporary artists, you want it to be not just a group show but a temporary world. And maybe this is why my exhibitions become bigger—because the inner world is getting bigger.

It is true that the changes you see with artists’ works are the best societal seismographs. Artists, like curators, work on their own, grappling with their attempts to make a world in which to survive. I always said that if I lived in the 19th century as King Ludwig II, when I felt the need to identify myself with another world I would build a castle. Instead, as a curator I do temporary exhibitions. We are lonely people, faced with superficial politicians, with donors and sponsors, and one must deal with all of this. I think it is here that the artist finds a way to form his own world and live his obsessions. For me, this is the real society.

![]()

View from the 1999

Venice Biennale. |

CT: At the end of the 19th century there was a schism between art and technology; at the end of the 20th century there was a reunion. Aside from pragmatic information, the Internet has become a fantasy, a dream machine for the wired masses and a catalyst for globalization. What do you think about the effect of this technological revolution?

HS: This new technology makes an illusion of globalization, but again it creates a social split between those who can use it and those who cannot. In art we still have to go see the original object and discuss it with the artist. New technology does not know how to deal with the erotic element, with art that is spatial. This was always a problem. Think of Robert Ryman: he was always reproduced badly, but the originals are beautiful. We’re finally very old-fashioned—we must go around looking at originals. This is absurd, but it’s beautiful. When I was a student, hundreds of us had to go through the same books to find certain masterpieces; we marked our findings with pieces of paper. With the Internet, it is easier not to have to look through a thousand books—wonderful! But with art itself, we must go to the three dimensions.

![]()

View from the 1999

Venice Biennale. |

CT: Mass production has been encroaching on the handmade for more than a century and was anointed into the art culture by Duchamp and Warhol. Now, in the computer age, the reproduction, the virtual, and the fictive have encroached further as products of information.

HS: Globalization would be perfect if it brought more justice and equality to the world, but it doesn’t. Artists dream of using computer or digital means to have contact and to bring continents closer. But once you have the information, it’s up to you what you do with it. Globalization without roots is meaningless in art.

CT: Do you mean, by “roots,” the individual narratives within the global village?

![]()

View from the 1999

Venice Biennale. |

HS: Well, yes. An artist like Jason Rhoades uses technology, but he brings it into the service of the personal, as in the evocation of his father’s garden. The art is a new interpretation of something that possesses him. Also, a lot of things on the Internet are verbal. Only five percent is visual. The majority of people look through the ear. The Internet is good for information, but it never replaces eye contact. It also overloads you with a lot of trash. In a recent interview, Jeff Bezos defined the Internet as a narrow horizontal level of competence over all industrial fields. He compared it with electricity at the beginning of the 20th century, increasing speed for some things while revolutionizing others. Also, the digital image has extended possibilities. For me it is mainly information, but not art in itself.

CT: Jason’s accumulations come across as a trash heap that camouflages a narrative.

![]()

View from the 1999

Venice Biennale. |

HS: That’s what I like about his work: he’s not isolating an object, ambiguous objects, “polybiguous” objects—he’s showing us that we all have the obsession to consume. All these objects in a structure are his obsessions. It’s no longer Duchamp’s pissoir, which is isolated. Accumulations were a revolt against Duchamp, but then, they too became objects, a strategy to make a new object—as in Jason’s case, albeit a temporary one. Of course you have inner rules, like a museum of obsessions in your head. Then there are the freedoms or constrictions that we have from place to place. For instance, I can work in the North as a freelance curator, but in the South, I must accept the position of director, as in the case of the Venice Biennale.

CT: You are considered the first independent curator. How did this occur?

HS: It was a rebellion aimed at having more freedom, because I already had eight years as Director of the Kunsthalle in Bern. Well, I was director, but we didn’t say director. We wanted to open up the institution as a laboratory, more as a confirmation of the non-financial aspect of art. Then I curated Documenta 5, which is considered the end of a career.

![]()

View from the 1999

Venice Biennale. |

CT: Yes, to curate this exhibition, more than others, is to open oneself up to enormous scrutiny.

HS: Frankly, if you insist on power, then you keep going on in this way. But you must throw the power away after each experience, otherwise it’s not renewing. I’ve done a lot of shows, but if the next one is not an adventure, it’s not important for me and I refuse to do it.

CT: Conceptually oriented installation art and the foregrounding of the histories of exhibition spaces suggest a democratization of art challenges the museum’s elitism. In 1986 you took over unconventional, frequently gigantic venues: former stables in Vienna, the Salpetrière hospital in Paris, the palace in the Retiro park in Madrid. You invited artists to set up dialogues between their work and the chosen spaces.

![]()

Work by Maaria Wirkkala. Artists selected for the 2001 Venice Biennale exhibition, “The Plateau of Mankind.” |

HS: In Venice I was glad I had white-cube spaces, but I also had the Arsenale, where the artists had to accept the historical space as it was. From the space problem came the question of the demand for objectivity and intervention, and how to give life to memory. During the last number of years in Venice, this was all about the survival of the institution of the Biennale. If you stay only in the Giardini, you maintain the nationalist aspect; for the institution to survive the 21st century, new spaces were needed.

CT: What does it mean to be Director of the Biennale after being an independent curator for so long?

HS: In Venice, only when you are Director can you show what you want. In ’95, I wasn’t Director and the planned exhibition “100 Years of Cinema” didn’t take place. I worked for the Biennale in different years; in 1975, I did “Bachelor Machines.” Of course, the contracts never came on time; I had to get money from a bank, and I paid the interest. Finally, I gave all museum contracts to the bank, and the museum paid the sum, which was 15,000 Swiss francs, directly to the bank. There are the usual delays in Italy with contracts, so we first started the exhibition in Bern, although it was produced for Venice. At this time I was taking over new spaces for art, specifically the Magazzini de Sal, the Salt Depository. In 1980, there were five curators. The theme was the ’70s. At that point I told them that we were in a moment when things were changing, so let’s not stop with Stella and the German painters. I told them we had to do Aperto or I would leave. The Aperto was not just a salon for artists under 35; I showed Richard Artschwager and Susan Rothenberg, Ulrike Ottienger and Friederike Pezold.

CT: The 1999 Aperto did not seem to focus only on young artists. Louise Bourgeois, Dieter Appelt, Dieter Roth, Franz Gertsch, and James Lee Byars were among your choices.

![]()

Work by Gerd Rohling. Artists chosen for the 2001 Venice Biennale exhibition “The Plateau of Mankind.” |

HS: The Biennale of 1999, d’APERTtutto, was more in the spirit of the first Aperto, not limiting “young” to artists under the age of 35. I have always thought that if biennials wanted a future, they should emulate the structure of Documenta. And today, the oldest biennial—in Venice—when faced with so many biennials, should be the youngest.

CT: At Documenta, finally, does the curator have autonomy from the bureaucratic duties?

HS: Until 1968, there was a huge Documenta council; its founder, Arnold Bode, was a “degenerate” painter under Hitler. They wanted to show Germany what it missed in the “thousand years” of Nazism. After 1968, the council became quite absurd. They were missing many important issues, and for this reason they asked me to be the artistic director. All the former Documentas followed the old-hat, thesis/antithesis dialectic: Constructivism/Surrealism, Pop/Minimalism, Realism/Concept. That’s why I invented the term, “individual mythologies”—not a style, but a human right. An artist could be a geometric painter or a gestural artist; each can live his or her own mythology. Style is no longer the important issue.

![]()

Work by Joseph Beuys. Artists selected for the 2001 Venice Biennale exhibition, “The Plateau of Mankind.” |

CT: In 1969 you curated the exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form: Live In Your Head.” It presented for the first time in Europe artists such as Beuys, Serra, and Weiner. With this exhibition, the process of creation was recognized as a work of art. It was also at this time that you became an independent curator.

HS: Yes, it was in March, only a couple of months after the end of Documenta 4, when I curated “When Attitudes Become Form.” How can you do this big exhibition, Documenta 4, and miss showing the works of new artists? So I did it in Bern in March. Of course, this made a big impact. Then I was asked to do the next Documenta with my own strategy. I dissolved the committee. It costs a lot to convene a committee of 40 people, and half are never present, anyway. Also it’s cheaper when one person travels to see colleagues and explore what is new in their region.